The technology for making stave barrels/tubs (oke 桶) advanced in the Muromachi period (Muromachi jidai 室町時代, 1336 - 1573), but the use of these as bathtubs didn’t spread to minka until the custom of bathing became widespread in the mid Edo period (Edo jidai 江戸時代 1603 - 1868). In minka in Kantо̄ (関東), the region of eastern Japan centred on Edo (Tо̄kyо̄), there were elliptical (da-en-gata 楕円形) bath tubs (furo-oke 風呂桶), often with a ‘jujube-shaped’ (natsume-gata なつめ型 or 棗型) iron kettle (tetsu-gama 鉄釜) built into them; varieties include the sue-buro (据え風呂, ‘squat/sit down bath’), oke-buro (桶風呂, ‘barrel bath’) and teppо̄-buro (鉄砲風呂 ‘gun bath’). These baths have no particular need for a bathroom (yoku-shitsu 浴室), so they could be installed in a corner of the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間), or outside, under the eaves.

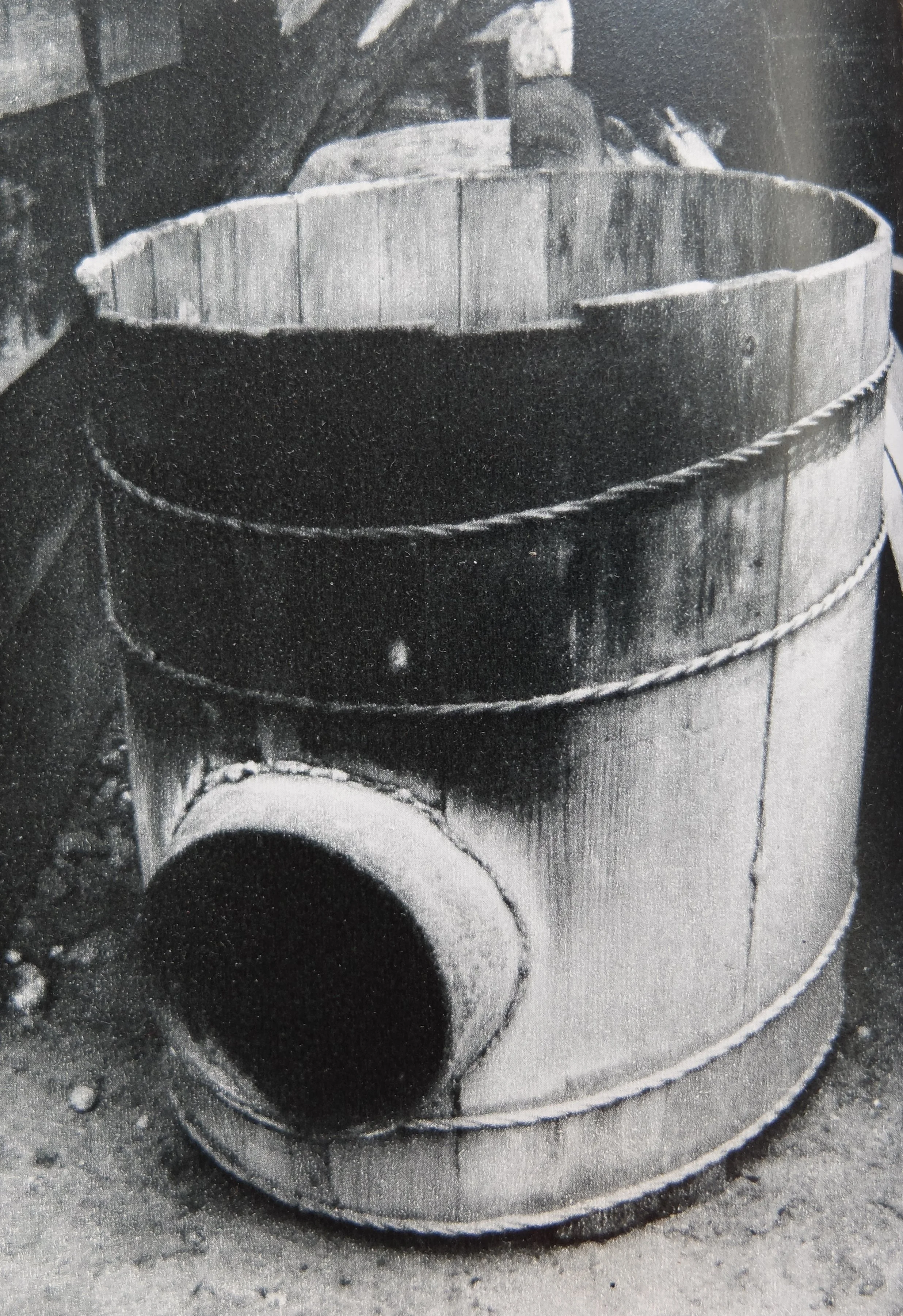

A primitive tub bath (oke-buro 桶風呂). There is no flue (endо̄ 煙道), only a large feeder opening (taki-guchi 焚口). Its efficiency is poor, requiring four or five hours to heat the water. Toyama Prefecture.

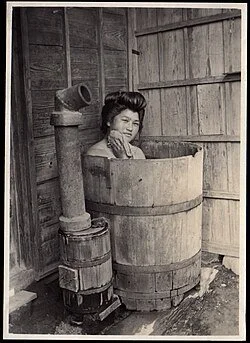

The ‘barrel bath’ or ‘tub bath’ (oke-furo 桶風呂) is portable, so can be set up in a corner of the doma, under the eaves outside as in this example, or elsewhere. Its kettle (kama 釜) has separate feeder opening (taki-guchi 焚口) and exhaust flue (endо̄ 煙道), and represents an improvement in efficiency over what came before.

A scene full of wild charm: an open-air bath (yaten-buro 野天風呂) screened by banana plants (bashou 芭蕉) on Amami (奄美) Island, Kagoshima Prefecture. Also known as kana-buro (鉄風呂, ‘iron bath’), in which the hot water kettle (yu-gama 湯釜) is used as-is as a bathtub (yoku-sо̄ 浴槽), with the fire directly underneath (jikabi-shiki 直火式, ‘direct fire type’). With the addition of a permanent stove (kamado 釜土) structure, this type of bath evolved into the Goemon-buro (五右衛門風呂); it can be seen that this style, together with the portable ‘tub bath’ (oke-buro 桶風呂), in which a heating apparatus (ka-netsu souchi 加熱装置) is attached to a hot water tub (yu-oke 湯桶), represent the two main paths of development of the ‘bathtub’ (yoku-sou 浴槽).

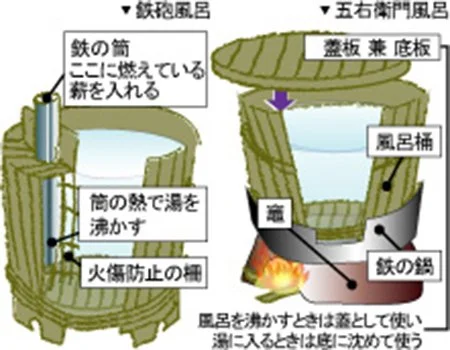

Two simple bath types. On the left, a teppо̄-buro (鉄砲風呂 ‘gun bath’), in which fuel is burnt in an iron tube (tetsu no tsutsu 鉄の筒), which transfers its heat directly into the surrounding water. The bather is protected from burns by a fence (kashо̄ bо̄shi no saku 火傷防止の柵, ‘burn prevention fence’). On the right, a Goemon-buro (五右衛門風呂), with stove (kamado 竃), iron pot (tetsu no nabe 鍋), bath tub (furo-oke 風呂桶), and a board (ita 板) which serves double duty, as a lid (futa-ita 蓋板) when the bath is being heated, then as the ‘bottom board’ (soko-ita 底板), placed in the iron pot so the bather can sit in it without being burned.

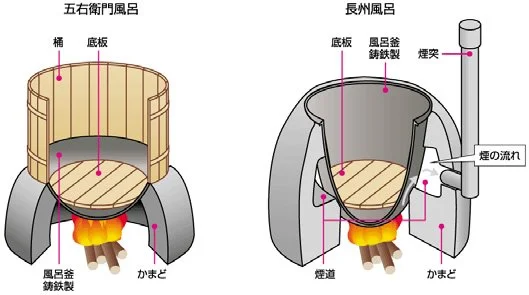

In contrast, in the Kansai (関西) region, broadly western Japan, there were many of what are called Goemon-buro (五右衛門風呂), baths in which water in a bathtub with a cast-iron (chūtetsu 鋳鉄) kettle at its base is heated by a fire directly below. It can burn straw, leaves and trash as fuel. The name derives from Ishikawa Goemon (石川五右衛門), a legendary bandit and Robin Hood-like outlaw folk hero of the Azuchi-Momoyama period (Azuchi-Momoyama jidai 安土桃山時代, 1573 - 1603) who was executed by boiling alive. Like the sue-buro, the Goemon-buro is not portable, and was built in a corner of the interior, outside, or in a dedicated bathroom (yoku-shitsu 浴室) in a detached bathhouse building. As indicated by another of its alternate names Chо̄shū-buro (長州風呂), from long ago the Goemon-buro was distributed in southern Chо̄shū (長州, present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture). According to some sources, the Chо̄shū-buro is distinguished from the Goemon-buro in that the former has a cast-iron cast-iron (chūtetsu 鋳鉄) bathtub (yokusо̄ 浴槽) and a flue (endо̄ 煙道), traditionally constructed of ridge tiles (muna-gawara 棟瓦) or stone

Left, a Goemon-buro (五右衛門風呂) with tub (oke 桶), bottom board (soko-ita 底板), cast-iron (chūtetsu-sei 鋳鉄製) ) bath kettle (furo-gama 風呂釜), and stove (kamado かまど). Right, a Chо̄shū-buro (長州風呂), with cast-iron tub/kettle, bottom board, ‘smoke path’ (endо̄ 煙道), stove, and chimney/flue (entotsu 煙突).

A Chо̄shū-buro built with natural stones with a dedicated bathroom (yoku-shitsu 浴室) built around it.

The sue-buro is thought to have developed from attaching a bathing (yu-ami 湯浴み) barrel (yutо̄ 湯桶) or tub (tarai 盥) to a kettle (kama 釜); while the ‘direct fire type’ (jikabi-shiki 直火式) bath like the Chо̄shū-buro, where a ‘stove’ (kamado 釜土) is built, is thought to have developed out of the kettle (kama 釜) of the kiln bath (kama-buro 窯風呂); in this too, the distinction between hot water (yu 湯) and bath (furo 風呂) seems acknowledged.

Old illustration of a sue-buro (据え風呂, ‘squat/sit down bath’)

A sue-buro in its bathroom setting. The bath is filled from the single cold tap. The fence separating the bather from the hot firebox is visible in the tib, as is the hole above the firebox for the flue, which is not attached. The low door allows the fire to be conveniently fed from outside with firewood stored under the eaves.

Today the majority of minka have their own bathing facilities, but in the past this was not the case. Several households might share a communal bath and heat it on a rota system, with firewood gathered collectively, called gо̄gi (合木, lit. ‘join wood’). There were also arrangements in which each house’s bath was heated in order, and residents would have the use of each others’ facilities, a practice called morai-buro (貰い風呂, ‘receive bath’). In these systems, it was more practical to establish bathhouse structures separate from their houses, as in the picture below.

A detached bath house with a ‘direct fire type’ (jikabi-shiki 直火式) bath, visible on the left, consisting of a wooden tub and shallow iron kettle, with firebox opening below. As a separate structure, the bath house is convenient for morai-buro (貰い風呂), the practice of villagers’ using each others’ baths in turn. Yamagata Prefecture.

As a method of making most efficient use of scarce hot water, a ‘hybrid’ style of bathing, combining hot water bathing and steam bathing, can be found from the east side of Lake Biwa in the Kinki region to the Hokuriku region. In this method of bathing, the bathtub (furo-oke 風呂桶) is deep; when one enters it and closes the lid, it can be sealed off; while washing with the hot water one also bathes in the steam. This method of bathing makes sense in drafty minka in the country’s cold-climate regions. The deep tubs are named after their form: yu-daru (湯樽 ‘bath barrel’), or also simply yu-uke (湯桶 ‘hot water tub’). Though the tubs themselves are deep, the level of water in them is only around 20cm; it is a ‘sealed style’ (mippei-shiki 密閉式) of bathing (nyū-yoku 入浴, lit. ‘enter bathe’) where the hot water is scooped up over one’s body; the method is also called iri-yu (居り湯; here iru 居る means ‘to sit’). On Sado (佐渡) Island, there are baths of the same kind, and the bathtub (furo-oke 風呂桶) is called oroke (おろけ), from iri-yu no oke (居り湯の桶 ‘tub of sitting hot water’).

A woman bathing in a barrel bath (oke-buro 桶風呂) with attached firebox and flue, 1911.

A woman bathing in a sue-buro, 1945.