The modern Japanese word for ‘bath’ is furo (風呂, lit. ‘wind spine’). The fu of furo refers to air (kūki 空気), and the ro here has the meaning of ‘surround’ or ‘enclose’ (kakou 囲う): furo originally indicated not a ‘bathtub’ or other container to hold hot water, but a relatively airtight room or space, through which air or wind (kaze 風) does not pass. It is in this sense of the word that, in the Hokuriku region, cupboards and toilets (water closets) are also called furo, or at least were until recent times.

In the regions surrounding the Seto Inland Sea (Seto-Naikai 瀬戸内海), there were from long ago furo called iwa-buro or ishi-buro (石風呂, ‘rock/stone bath’). These baths probably originated when sailors (ama 海士), needing to warm themselves, burned driftwood in rock pools. Later, firewood was burnt in enclosures (kake 郭) constructed of stone; once the stones had heated up, the fire was raked out, water was poured onto the perimeter wall, and people took straw mats soaked in seawater into the enclosure, to sit enveloped in ‘steam’ (jо̄ki 蒸気) and hot air (nekki 熱気). These enclosures were usually around eight jо̄ (帖), or 13m², in size, with an entrance around 90cm high and 60cm wide, hung with a mat (mushiro 莚). The exterior side of the stone wall was plastered with earth, and a roof structure was added to keep wind and rain out, and heat and steam in. Bathers did not bathe naked, but in old clothes. This type of bath is distributed across the coastal areas of Yamaguchi, Hiroshima, Okayama, Ehime, and Kagawa Prefectures. Its exact origins are unknown, but it is thought to have come from central Asia via Korea (Chо̄sen 朝鮮). There are places where iwa-buro were still in use until recently, such as one on the outskirts of Imabari City (Imabari-shi今治市), Ehime Prefecture, which may still operate sporadically as a volunteer-staffed tourist attraction.

Primitive bath types.

Left, a ‘salt bath’ (shio-furo 塩風呂). At around 2.7m in height, it is somewhat larger than the Yase kiln bath, but its method of firing and entry are essentially the same. Pine branches are burnt in it, then grass mats soaked in salt water are laid down.

Middle: the Yase ‘kiln bath’ (kama-buro 窯風呂), around 1.8m in height, with a floor area of around three tatami mats, or about 5m2. The floor is laid with flat stones.

Right: a ‘stone bath’ (iwa-buro 石風呂) in Sakurai, Imabari City, Ehime Prefecture, made by hollowing out a natural rock hill. The front slope has been stabilised with concrete.

The Kishimi stone bath (Kishimi ishi-buro 岸見石風呂) in Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Similar in type to the iwa-buro is the ‘kiln bath’ (kama-buro 窯風呂), as in the example in Rakuhoku Yase (洛北八瀬), Kyо̄to City, shown in the image below. This is completely dry hot-air bathing (nekki-yoku 熱気浴) or ‘sweat bathing’ (hakkan-yoku 発汗浴), where the low humidity promotes and optimises the effect of sweating. The relationship of this bath to the iwa-buro is not clear, but in form it is identical to a charcoal kiln (sumiyaki-gama 炭焼窯), and it is reasonably surmised that the idea for the kama-buro came soon after the advent of sumiyaki-gama and pottery/ceramic kilns (tо̄yо̄ 陶窯). Regardless, both iwa-buro and kama-buro are comparatively large-scale in their construction and operation; their interiors are completely dark; their entrances are narrow, and getting in and out of them is awkward: they are primitive in every aspect.

An old kiln bath (kama-buro 窯風呂) preserved in Rakuhoku Yase, Kyо̄to Prefecture.

Steam baths (mushi-buro 蒸し風呂), which accompanied Buddhism to Japan from the continent, are a step more advanced: large iron pots/kettles (tetsu-gama 鉄釜) are used to heat the water, and structures in with various architectural features grew up around them. Famous examples are the ‘warm rooms’ (on-shitsu 温室), essentially sauna, of Hо̄ryūji (法隆寺), Daianji (大安寺) and Saidaiji (西大寺) temples, and the ‘Tang bath’ (kara-furo or kara-buro 唐風呂) of Hokke-ji (法華寺) temple, though in this particular example kara-furo is written 浴室, which is normally read yoku-shitsu (‘bathing room’). Of course these baths were used by the monks and the noble guests they entertained, but they were also open to the general public for bathing while traveling (tabi-yoku 旅浴) or on pilgrimage. These bathing houses are constructed such that within the grand outer building there is a smaller, house-like, gable-roofed structure with a raised ‘grating’ (sunoko 簀の子) floor covered with mats (goza 茣蓙); to its rear is the kama-ba (釜所), the space for the large hot water kettle or cauldron (yu-gama 湯釜), arranged so that steam and heat are drawn under the floor and up into the inner structure.

Illustration showing the operation of the kara-furo (唐風呂) ‘bathroom’ (yoku-shitsu 浴室) of Hokke-ji (法華痔) temple. Labelled are the kettle (kama 釜), ‘steam’ (jо̄ki 蒸気), grating floor (sunoko スノコ), floor mats (goza ゴザ), cypress (hinoki ヒノキ) fragrant wood (koboku 香木) as herbal medicine (shо̄yaku 生薬), ‘water place’ (mizu-ba 水場), and entry/exit (de-iri-guchi 出入口).

Exterior view of the kara-furo (浴室) of Hokke-ji temple.

Interior view of the kara-furo (浴室) of Hokke-ji temple.

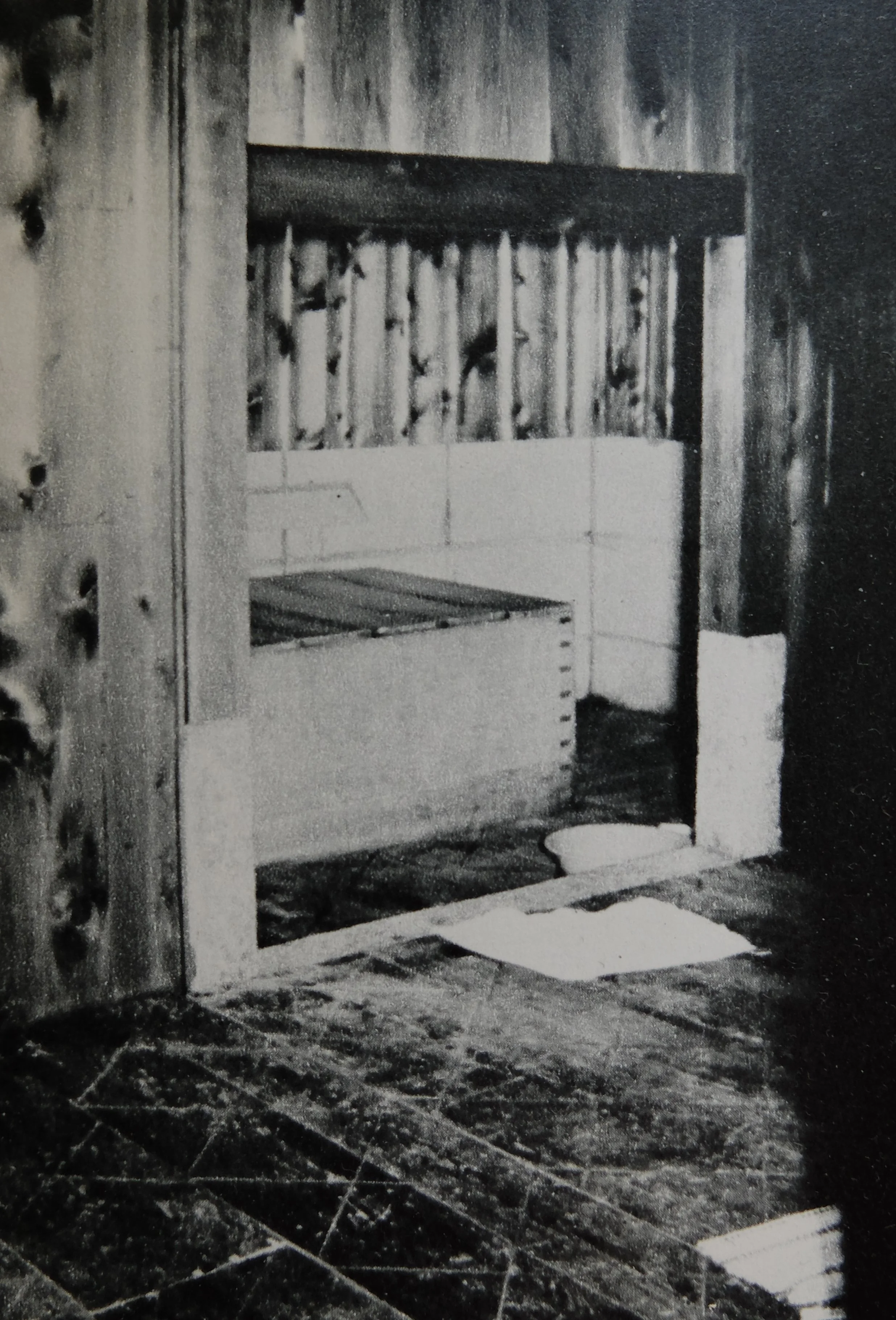

As mentioned, the earliest public baths (sento 銭湯) were also of the steam-bath type (mushi-buro keishiki 蒸し風呂形式); so humidity and heat did not escape, there was a board wall between the ‘changing room’ (datsui-shitsu 脱衣室) and the bath room (yoku-shitsu 浴室), with a low, gate-like entrance called a zakuro-guchi (ざくろ口 ‘pomegranate door’) through which people had to crawl to enter. This arrangement is effective in preserving temperature, so it survived even after the change to hot water bathing (onyu-yoku 温湯浴). The image below shows a zakuro-guchi style bathroom entry surviving in an inn (hatago-ya 旅籠屋) in Kiso (木曽). In the past, mirrors were polished with pomegranate vinegar, and presumably the name zakuro-guchi arose because the frame of the tiny entrance would be polished to a mirror finish by the bodies of those squeezing through it.

A zakuro-guchi (ざくろ口) entrance in the bathroom (yu-dono 湯殿) of a reconstructed inn (hatago-ya 旅籠屋) in Kiso, Nagano Prefecture. The zakuro-guchi prevents the dispersal of steam; in the past these entrances were even smaller. The yu-dono has a wainscot of stone cladding, and the floor is laid with timber boards that are scored to prevent slipping.

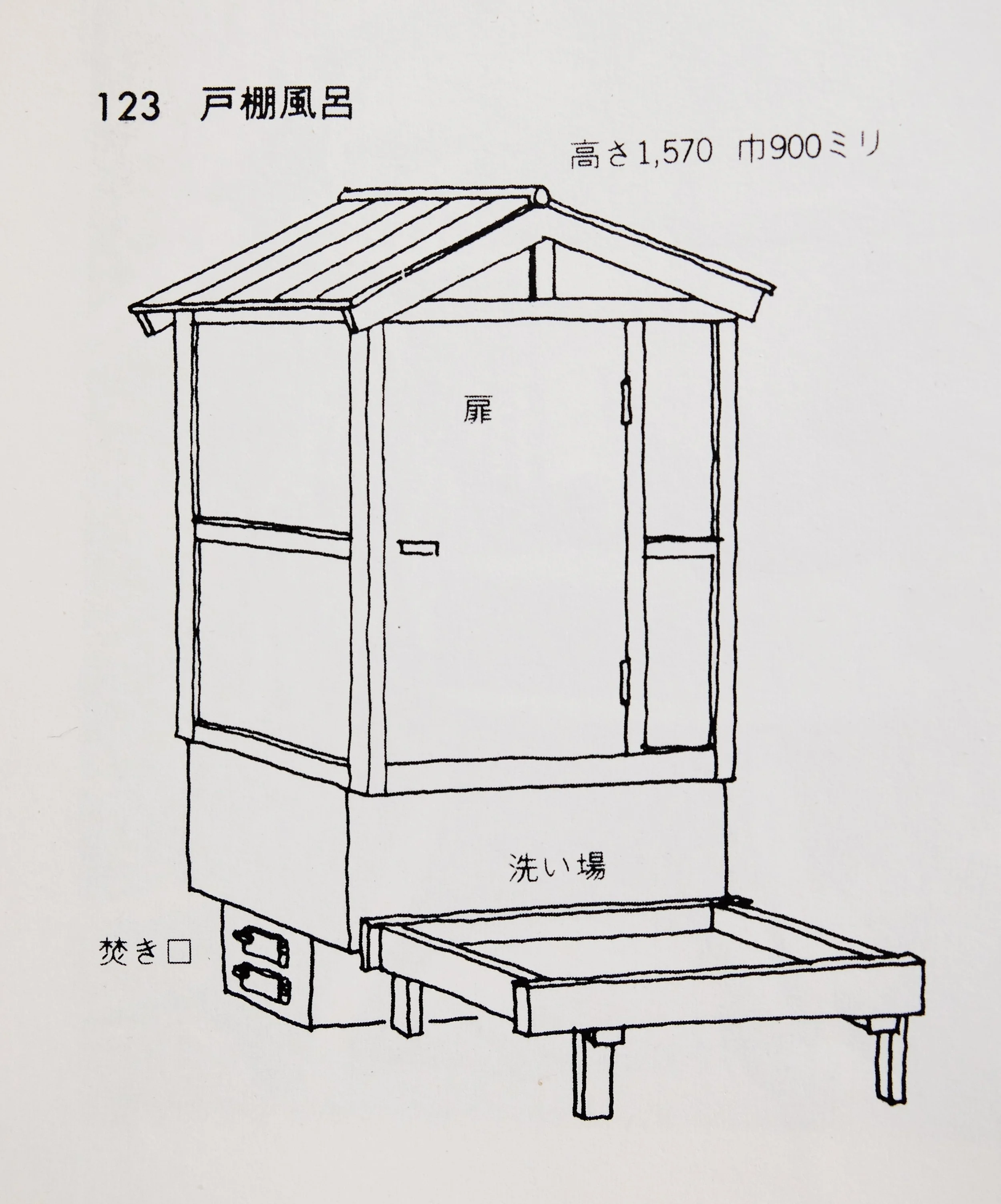

At some point there appeared steam baths for individual, domestic use, called todana-buro (戸棚風呂, ‘cupboard bath’), which were fitted with a wooden door (to 戸) to retain heat and steam.

Illustration of an individual steam bath for private domestic use, the todana-buro (戸棚風呂, ‘cupboard bath’). Labelled are the door (to 戸), the ‘washing place’ (arai-ba 洗い場), and the firebox door (taki-guchi 焚き口).