There are two types of non-ritual or ‘hygienic’ bathing (nyūyoku 入浴, lit. ‘enter bathe’) in Japan: hot water bathing (ontо̄-yoku 温湯浴, lit. ‘warm-hot water-bathing’) and steam bathing (jо̄ki-yoku 蒸気浴, lit. ‘steam-air-bathing’). The public bath (sentо̄ 銭湯) is called the furo-ya (風呂屋, lit. ‘bath house’) in Kansai, and yu-ya (湯屋, lit. ‘hot water house’) in Kantо̄, and the room containing the bath (yoku-shitsu 浴室, lit. ‘bathing room’) is called the furo-ba (風呂場, lit. ‘bath place’) or yu-dono (湯殿, lit. ‘hot water hall’), but the conflation or melding of yu (湯, hot water) and furo (風呂, bath) did not begin until the middle of the Edo period (Edo jidai 江戸時代, 1603 - 1868). It was at around that time that public baths appeared in Edo; at first these were for steam bathing (jо̄ki-yoku 蒸気浴), but before long they had switched to hot water bathing. Furo originally referred to steam-bath type (mushi-buro keishiki 蒸し風呂形式) ‘sweat bathing’ (hakkan-yoku 発汗浴), while yu meant ‘immersing oneself in heated water’ (ontо̄-yoku 温湯浴).

The Japanese language has different words for cold water (mizu 水) and hot or heated water (yu 湯). The etymological origin of yu (湯, hot water) is said to be 斎 yu, a reading that survives today only in names; today 斎 is typically read sai, meaning (religious) purification or purity (shо̄jо̄ 浄清). There is the term saikai-mokuyoku (斉戒沐浴), ‘purity admonition ablution bathing’ undertaken before Buddhist or Shintо̄ prayer or other sacred activities, but this is done in a natural (flowing) body of water, i.e. a river or stream, or at a man-made facility such as a well, without regard to the water temperature; mokuyoku/yu-ami (沐浴) means to bathe (mizu-abi 水浴び) in order to purify the body (mi wo kiyomeru 身を清める). Bathing in naturally-occurring hot springs (onsen 温泉) and bathing in hot water were originally undertaken for recuperative or therapeutic (ryо̄yо̄ 療養) aims; long ago, this bathing (nyūyoku) was done wearing a kata-bira (帷子): a thin, unlined robe. As the purpose of bathing gradually shifted towards purifying (jо̄ketsu 浄潔) the body (shintai 身体), bathing came to be undertaken naked.

Gyо̄zui, transferring heated water to a tub (tarai 盥) and washing in it, is the simplest form of hot water bathing, but as indicated by old terms like sensoku/sensuku (洗足 lit. ‘wash feet’), by which gyо̄zui is known in some regions, it was not initially full-body bathing (zenshin-yoku 全身浴).

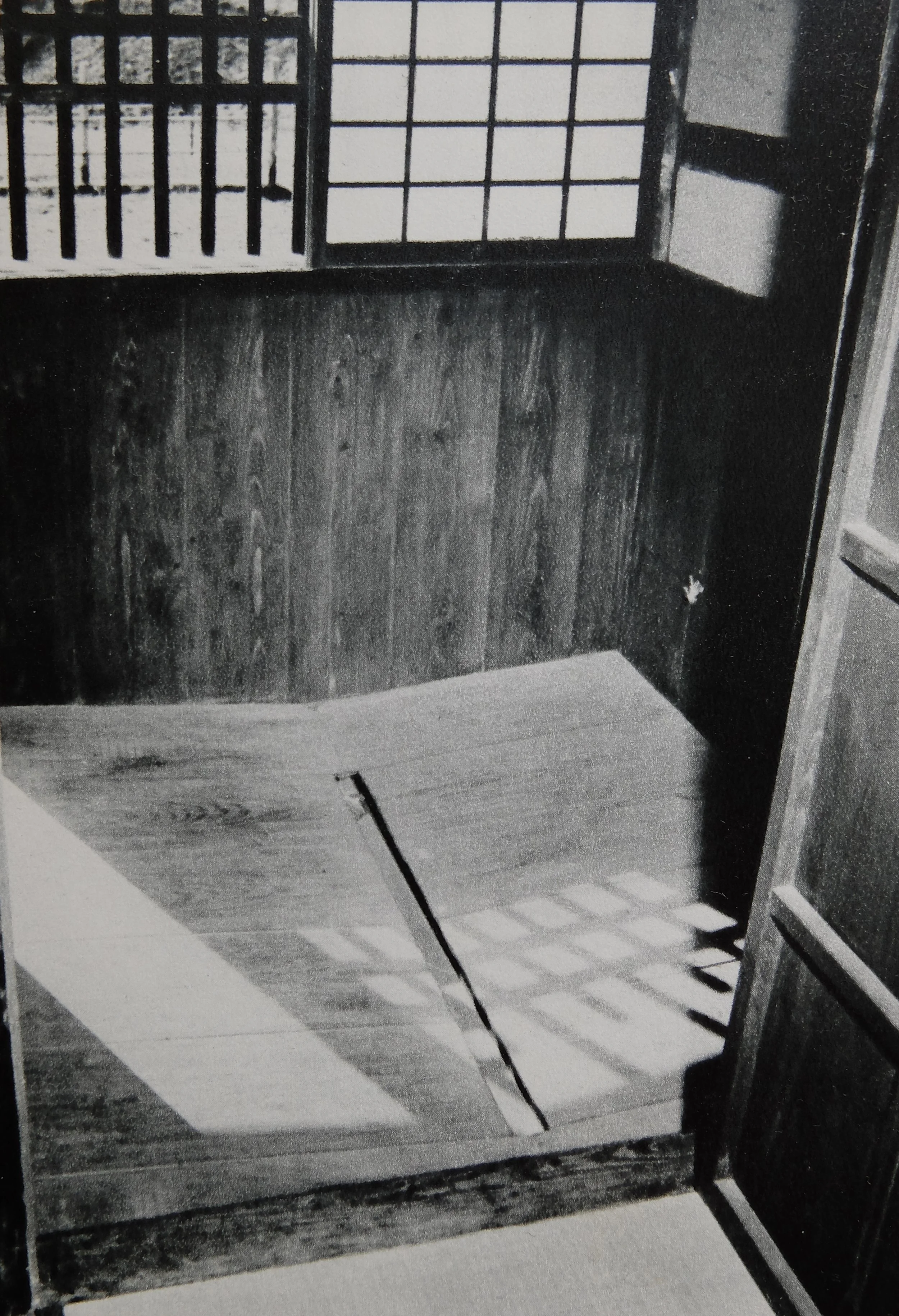

The yu-dono (湯殿, lit. ‘bathing hall’), the ‘bathroom’ (yoku-shitsu 浴室) built as a separate structure in the shinden-zukuri (寝殿造り) residential complexes of the nobility, was also a facility for heated water mokuyoku. This style of bathroom survived in minka, in the form like that seen in the image below. For the convenience of drainage, the floor boards are given a fall, but otherwise there are no fixtures or fittings.

In a yu-ami style (yu-ami keishiki 湯浴み) ‘bathroom’ (yu-dono 湯殿), there are no facilities or fixtures whatsoever, other than the fall given to the floorboards to ensure good drainage. Of those that survive, many are used as storage rooms. Former Sasaki family (Sasaki-ke 佐々木家) residence, Nagano Prefecture, now relocated to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum (Nihon Minka-en 日本民家園), Kanagawa Prefecture.

In the farmhouses of the Iya-dani (祖谷) region of Shikoku, bathroom (yokushitsu 浴室) and toilet (benjo 便所) were built projecting out from the centre of the south-facing facade (omote-gawa 表側), into and beyond the ‘verhandah’ (en 縁). A hole is opened in one part of the bamboo grate (takesu 竹簀) floor to serve as a urinal (shо̄benjo 小便所); the rest of the space is used as a facility for bathing (gyо̄zui 行水) and foot-washing (sensoku 洗足) on returning from the fields (nora-gaeri 野良帰り).

In most minka in the Iya-dani region of Shikoku, the toilet and bathing place project out from the centre of the southern facade. Nishimoto family (Nishimoto-ke 西本家) residence.

In the same way, in one part of the Chūgoku (中国) region, a bathing place (furo-ba 風呂場) and toilet (benjo 便所) are located beside the entrance (toguchi-waki (戸口脇) to the doma, at one end of the facade-side verandah (en 縁); often there is also a large fertiliser pot there. This facility is in front of the zashiki and close to the entrance, and one might think that the smell would be terrible, but a more important consideration was to position it on the southern, sun side, where decomposition was faster and good fertiliser (koyashi 肥し) could be obtained.

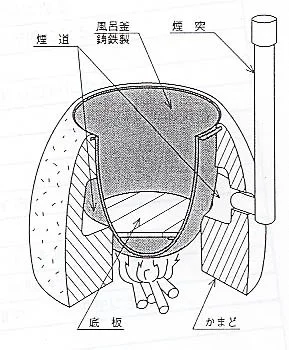

A toilet and bath established on the zashiki engawa. The bathroom flanks the entrance on the right. The bath is a ‘flue heated type’ (endо̄-kanetsu-shiki 煙道加熱式), called a Chōshū bath (chōshū-buro 長州風呂). The bathwater drains into the ‘toilet pot’ (ben-ko 便壷), also known as the ‘fertiliser pot’ (koe-tsubo 肥壷), to be used along with excreta as fertiliser (hi-ryō 肥料). This pot is called a kago-tsubo (カゴ壷); it is almost two metres in diameter, and is secured in place with red clay (aka-tsuchi 赤土). Hyōgo Prefecture.

A Chōshū bath (chōshū-buro 長州風呂) of the type used in the minka shown above.