In the О̄mi (近江) district, current-day Shiga Prefecture, there were many different styles of bathing, including one called mugi-buro (むぎぶろ), which was common in the peasant houses of the Kotо̄ Heiya (湖東平野), the plain east of Lake Biwa. Mugi (むぎ) is the Japanese word for barley, so the name may be in reference to the shape of a barley grain, or perhaps mugi is a dialect variant of mushi (蒸), ‘steam’. In the illustration shown below, a low stove (kamado 釜土) is fitted with a shallow, plate-like iron kettle (kama 釜), and on this rides the tub (yu-daru 湯樽 or yu-uke 湯桶). The joint is are packed with Japanese cypress (hinoki 桧, Chamaecyparis obtusa) bark and bedded down with plaster (shikkui 漆喰). The barrel is fitted with a door of around 50cm x 70cm in size, with a glazed viewing window. A duck board (fumi-ita 踏板 lit. ‘tread board’) is placed in or over the kama at the bottom of the tub. When closing the door and pouring hot water over oneself, the inside of the tub is sealed off, and the bath becomes a kind of steam bath.

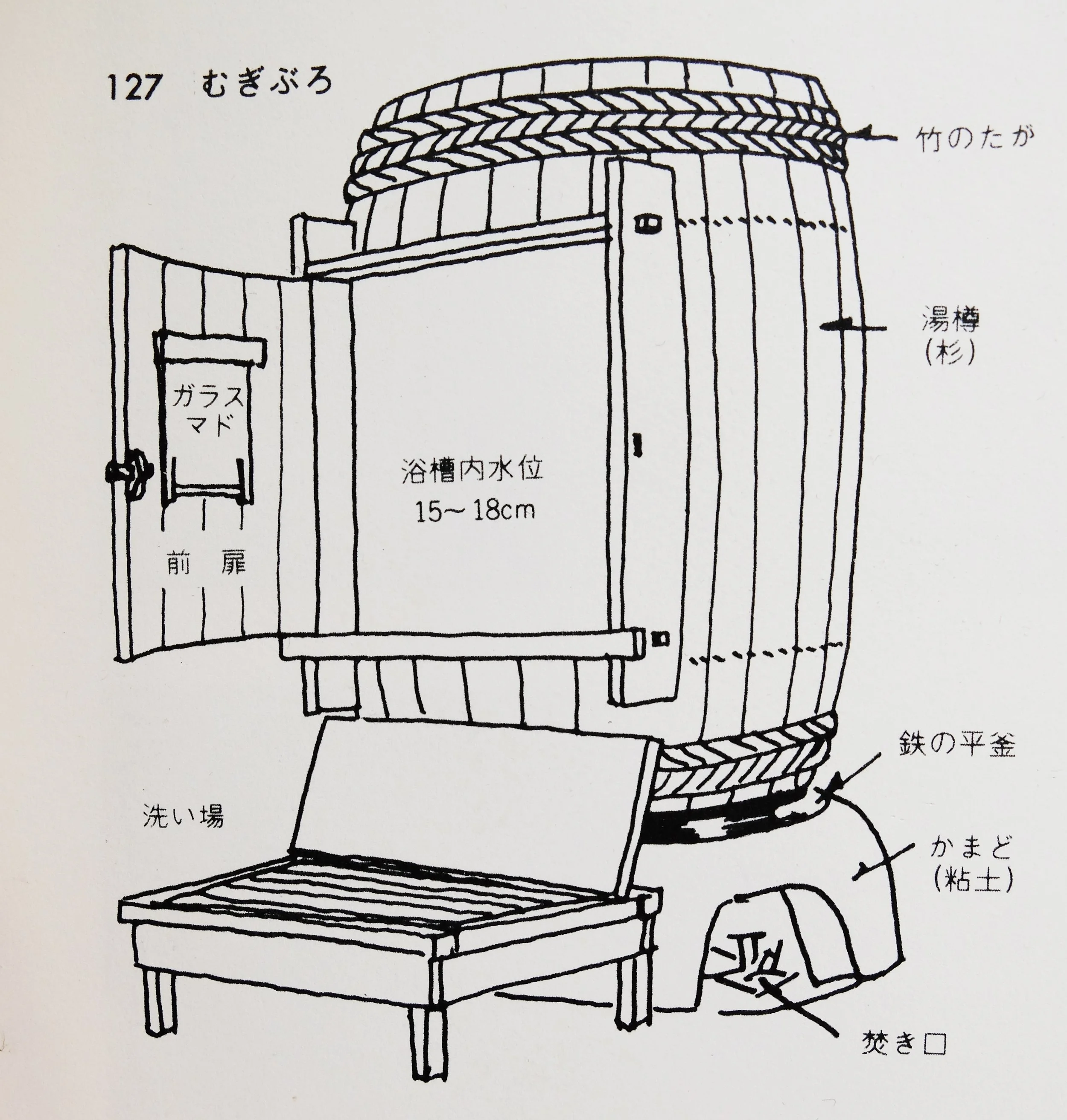

A mugi-buro (むぎぶろ). The water level in the tub (yokusо̄-nai sui-i 浴槽内水位) can only be as high as the door sill, so the water level is very shallow (15 - 18cm). Labelled are the ‘washing place’ (arai-ba 洗い場), clay (nendo 粘土) stove, (kamado かまど) stove mouth (taki-guchi 焚口), cypress (sugi 杉) tub (yu-daru 湯樽), and bamboo hoops (take no taga 竹のたが). Shiga Prefecture.

A mugi-buro or oke-buro (桶風呂) in use. Labelled are the ‘steam’ (jо̄ki 蒸気), hot water (yu 湯), ‘bottom board’ (soko-ita 底板), ‘flat kettle’ (hira-gama 平釜), fire (hi 火), and stove (kamado カマド).

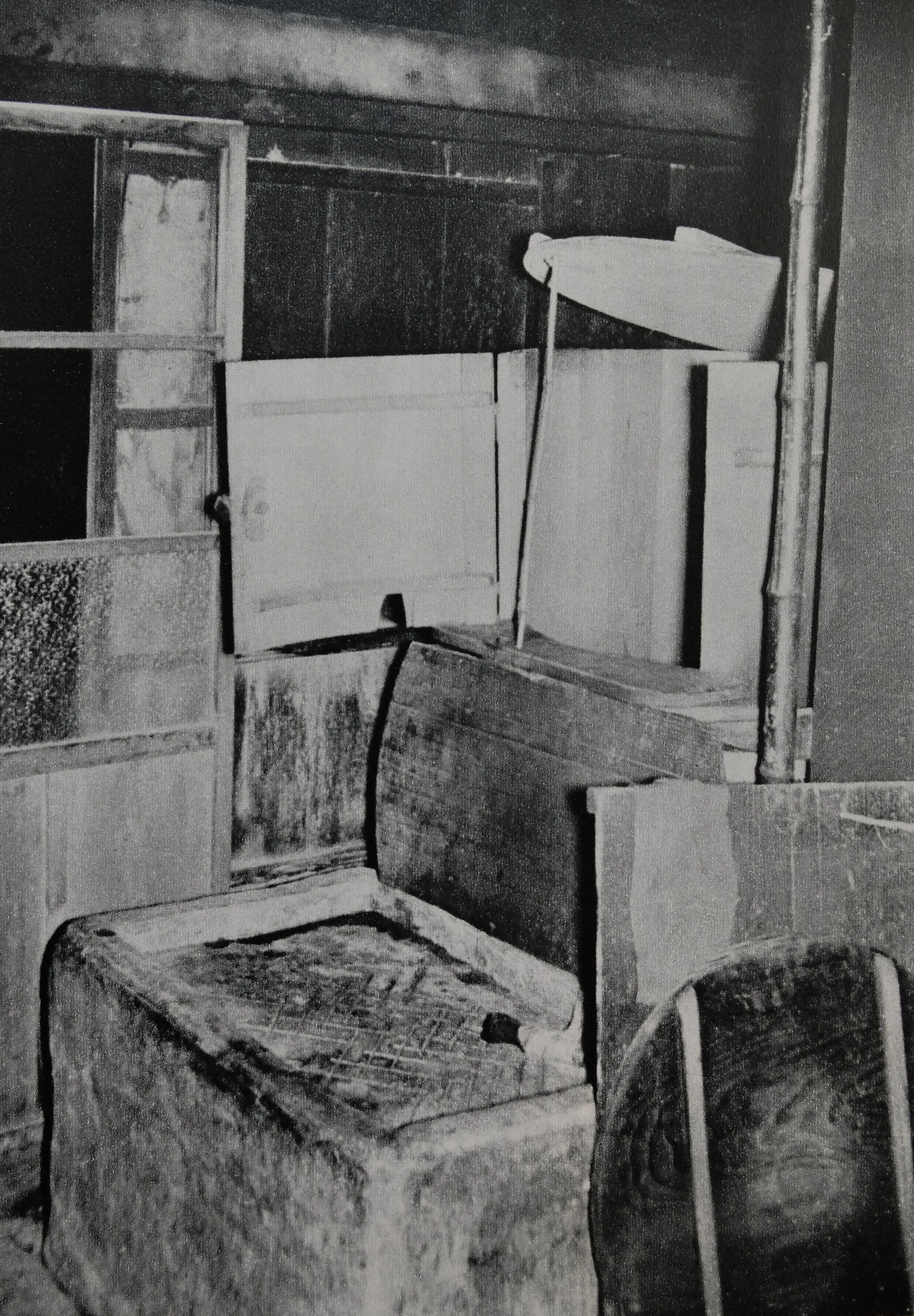

In the area north of Lake Biwa, there is a common type of bath in which the tub is low, but the lid over it can be opened and closed freely with a thin bamboo pole, effectively ‘sealing’ the tub. In this type of bath, too, the water level is shallow, as the tubs can only be filled up to the lower edge of the door opening.

This bath is also a type of mugi-buro, but not as closely sealed as the previous example. After opening the hinged door at the front and entering the tub, one operates the thin bamboo stick propping up the lid to close it. Uemi family (Uemi-ke 上見家) residence, Shiga Prefecture.

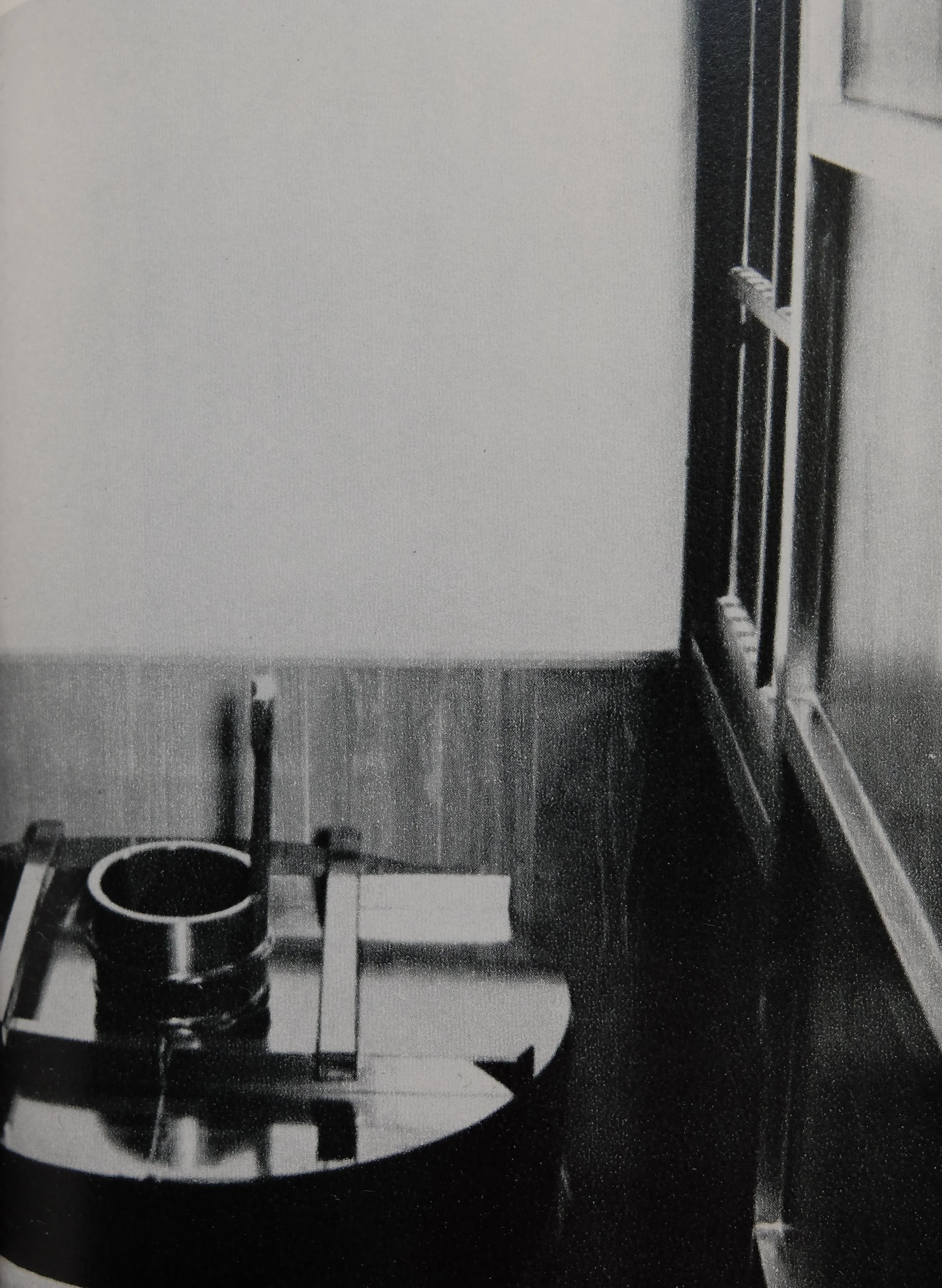

A lacquered (urushi-nuri 漆塗り) bathtub (yu-uke 湯桶). Because lacquer would be damaged by the heat of a stove-type or attached-firebox system, the tub is filled with hot water that has been heated elsewhere. Sakurai family (Sakurai-ke 桜井家) residence, Ishikawa Prefecture.

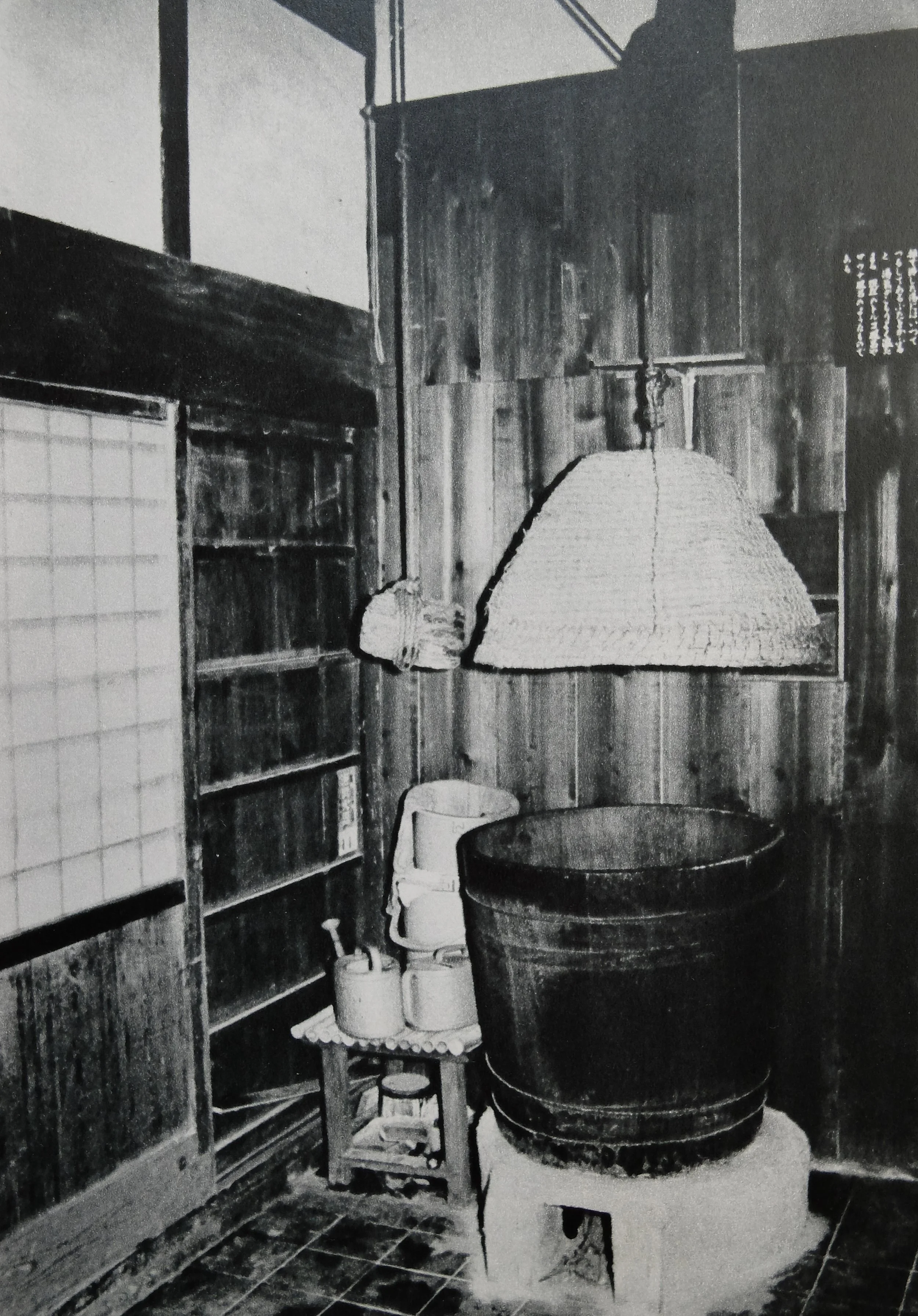

In the Suzuka foothills (Suzuka sanroku 鈴鹿山麓), an area known as Yama-no-ue (山の上, ‘above the mountains'), another type of bath, called tobi-komi furo (飛込み風呂, ‘jump into bath’), has no door, and the tub must be entered from above. As seen in the picture below, the tub (yu-uke ゆうけ) is capped with an inverted basket (fugo 畚) woven from straw; the type is also known as a fugo-buro (ふごぶろ ‘basket bath’). The basket is also called shiuta (しうた), an abbreviation of noshi-futa (載し蓋, ‘place on cap’).

A fugo-buro (ふごぶろ ‘basket bath’) in the Suzuka foothills (Suzuka sanroku 鈴鹿山麓). One enters the bath then lowers the lid from above to ‘steam’. The basket bath is a ‘flat kettle direct fire type’ (hira-gama choku-bi shiki 平釜直火式), but was originally a simple ‘unfired’ type, filled with hot water heated elsewhere. Nose family (Nose-ke 野瀬家) residence, Shiga Prefecture.

The bath below is from the Iga (伊賀) region of the Suzuka foothills. The baths known in Sado as komo-kaburi (こもかぶり, lit. ‘woven straw mat-wear on head’) are of the exact same type; the lid (futa 蓋), as in the Iga type, takes the form of a sedge hat (suge-gasa菅笠). In this example the basket is hung from a string on a pulley suspended from the ceiling, balanced with a counterweight so that it can be operated with a single finger. Both types were once simple tubs into which water heated on a stove was poured; they were later improved into the direct-fire Goemon-buro type.

This bath is of the same type as the one shown above, but with a pulley and counterweight mechanism to make raising and lowering the basket easier. The basket (shiuta (しうた 載蓋) is, like those used on Sado Island, is in the shape of a sedge hat (suge-gasa 菅笠).

A fugo-buro with the tub (yu-daru 湯樽) removed, showing the low stove (kamado 釜土) and ‘flat kettle’ (hira-gama 平釜). The bath is set up in the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間), near the back door (sedo-guchi 背戸口). Shiga Prefecture.

In addition to the types described above, there is the formal ‘upper bathroom’ (kami-yokushitsu 上浴室) attached to the upper formal room (kami-zashiki 上座敷) of designated inns (honjin 本陣) and the houses of wealthy farmers (gо̄nо̄ 豪農): hot water bathing (yu-ami 湯浴み) bathrooms that were in most cases called the yu-dono (湯殿 ‘bathing hall’) or yu-ba (湯場 ‘bathing place’). These might be a simple room with floorboards laid to a fall to drain water; or they mightbe located in a part of the doma paved with ceramic or clay tiles, with a bench-form (endai-jо̄ 縁台状) tray laid with a bamboo grate (takesu竹簀), and a tub (yu-uke 湯桶) and water bucket (mizu-oke 水桶) set up at its side. Or, as in the Nijо̄ jinya (二条陣屋), a townhouse (machiya 町家) in Kyо̄to, dating to around the end of the 18th century, there is a tiled and plastered bath (yokusо̄ 浴槽; yokusо̄ can also be translated as ‘bathroom’ or ‘bathing area’) with a ‘cove’ that holds a charcoal fire which heats water to recirculate via convection through holes in the tiles. Heating systems that work on this principle are still used today in modern baths.

The bathroom at Nijо̄ jinya (二条陣屋), Kyо̄to.

A relatively modern system that operates on the principle of convection, with two pipes circulating water between the bathtub and a detached iron stove.