Chūmon-zukuri (中門造り, lit. ‘middle gate style’) is a style of minka distributed along the Japan Sea coast, from the northern edge of Nagano Prefecture to the Tо̄hoku region, and is common in Akita Prefecture, from the centre of that Prefecture south. The minka of tenant farmers (ko-sakunо̄ 小作農) in these areas were ‘straight houses’ (sugo-ya 直屋造り), but those of farmers who owned their own land (ji-sakunо̄ 自作農) were L-plan (eru-ji-gata heimen L字型平面) ‘single chūmon style’ (kata-chūmon-zukuri 片中門造り) buildings, with the short leg of the L (the chūmon 中門), containing a stable (umaya 厩) and everyday entrance (tsūyо̄-guchi 通用口), projecting out from the façade side of the main building (omo-ya 主屋). Among the landlord class (jinushi-sо̄ 地主層), a second projecting chūmon was built in front of the formal room (zashiki 座敷), to form a U-plan (afu-ji-gata or о̄-ji-gata 凹字型) ‘double chūmon style’ (ryо̄-chūmon-zukuri 両中門造り).

The house of a wealthy farmer in Kana-ashi (金足), Akita Prefecture. There is no ‘front awning’ (mae-bisashi 前庇); the jettied (segai せがい) main roof is cut and folded upwards in a beautiful curve at the ‘lion window’ (shishi-mado 獅子窓). This house resembles the famous Nara house (Nara-ke 奈良家), an Important Cultural Property, but with its single chūmon (kata-chūmon 片中門) is more farmhouse-like in style.

A double chūmon (ryо̄-chūmon 両中門) minka in the suburbs of Akita City. The ridge is ornamented with kura-ki-gushi (鞍木ぐし, lit. ‘saddle timber comb’).

The double chūmon (ryо̄-chūmon 両中門) minka in the vicinity of Kana-ashi (金足) have upper chūmon (kami-chūmon 上中門) with gabled (kiri-tsuma tsukuri 切妻造り) and shingled (kokera-buki 柿葺き) roofs, and many have ‘rainbow beams’ (kо̄ryо̄ 虹梁) and other structural roof members visible in the gable, as in this example. There is no ‘lion window’ (shishi-mado 獅子窓) in the facade plane of the larger thatched chūmon roof; above the entrance is a gabled ‘snow awning’ (yuki-yoke hisashi 雪除け庇).

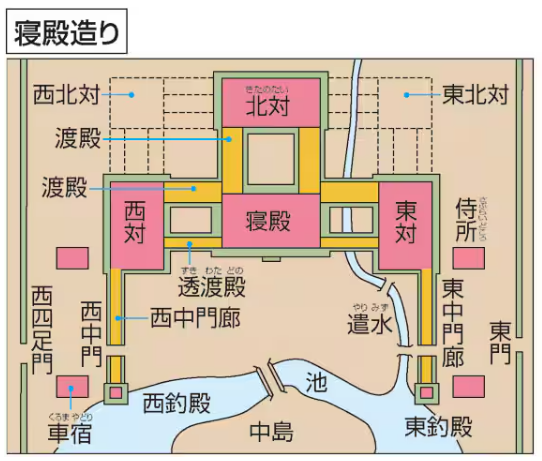

The name chūmon is also found in the shinden style (shinden-zukuri 寝殿造り) villa complexes of the Heian period, in the form of the chūmon-rо̄ (中門廊), the passageway that projected perpendicularly (kagi-no-te 鍵の手, lit. ‘key hand’) from the main building (omo-ya 主屋); it is apparently from a resemblance to this style that the chūmon of minka acquired the name.

A shinden-zukuri (寝殿造り) villa complex with east and west chūmon-rо̄ (中門廊) labelled.

People local to the areas where the chūmon-zukuri minka are found, however, do not refer to their dwellings as chūmon-zukuri as a style; instead, the word chūmon indicates a particular place within the house: the part in front of the zashiki, which is called the chūmon regardless of whether or not this part projects. In contrast, the projecting part that contains the stable is qualified with the term ‘stable chūmon’ (umaya-chūmon 厩中門), a name that appeared around the middle of the Edo period; but this too is often simply called the magari (曲り, lit. ‘bend’) in these areas.

In the façade wall of the umaya-chūmon is the everyday entry (tsūyо̄-guchi 通用口), called in local dialect the odo-no-guchi (おどの口, from о̄-do-guchi 大戸口, lit. ‘big door mouth’), or in architectural terminology the chūmon-guchi (中門口). On entering, normally the inner side of the chūmon is taken up by the doma passage (doma-rо̄ka 土間廊下) that leads to the main building (omo-ya), while the outer side is occupied by the stable, urinal (shо̄ben-jo 小便所), etc. At the ‘head’ or outermost part of the projecting chūmon is built a half-height upper storey (chū-ni-kai 中二階) called the fudara (ふだら); in winter, when the ground floor is buried in accumulated snow, the fudara is the brightest part of the house, so was used as a workshop for straw craft (wara-shigoto 藁仕事, lit. ‘straw work’) and other activities; it was also used as the sleeping place for the young men (wakaze 若勢) or manservants (otoko-shi 男衆) of the household, or for storage. If the snow was especially deep, the chū-ni-kai window was used as the entry to the house. More recently, the umaya is used as a garage for cars or rice seedling transplanters (saiten-ki 栽転機), and the chū-ni-kai is often renovated to serve as a children’s study or a bedroom for a young married couple.

To cater to the needs for light in the inhabited chū-ni-kai, the façade side of the chūmon roof is made either a clipped gable (han-giri-tsuma 半切妻, ‘half gable’), also known as a hakama-goshi yane (袴腰屋根, ‘hakama waist roof’ or kabuto yane (甲屋根 ‘helmet roof’); or a gable roof (kiri-tsuma yane 切妻屋根), in dialect kiri-ya (きりや) or kiri-me (きりめ). The window installed in this façade can also be found in minka in other regions, such as the taka-happо̄-zukuri and gasshо̄-zukuri; in the chūmon-zukuri, the ‘jetty’ (segai せがい) of the eave is ‘cut up’ (kiri-ageru 切り上げる) to form a ‘lantern window’ (akari-mado 灯り窓) called a shishi-mado (獅子窓). The thatching of the façade-facing roof plane of the chūmon is highly characteristic in its designs. Uniquely in this region, to keep the rain off the shishi-mado, the section of the roof above it is thatched out more thickly and clipped into a kind of eave (ama-yoke 雨避け, ‘rain averter’). The name shishi-mado comes from the resemblance of the form as a whole to the face of a lion (shishi 獅子); in the local dialect the name can also be heard pronounced susu-mado.

On passing through the the chūmon-guchi, there is a large ‘atrium’ (fuki-nuki 吹抜き) earth-floored utility area (doma-niwa 土間庭) used for agricultural tasks; in one corner of this doma, adjoining the stable (umaya), is a firepit (niwa-irori にわいろり) and a large stove (о̄-kamado 大かまど). Behind this in many cases there is a ‘sink place’ (nagashi-ba 流し場) for cooking that projects out into the perimeter eave space (geya 下屋); this is called the mijiya-no-ya (みじやのや), i.e. the mizu-ya 水屋 ‘water hut’). Next to the sink is the back door (ura no guchi 裏の口); between it and the inabe (稲部屋 ina-beya, ‘rice room’) at the rear facade (ura-shо̄men 裏正面) is a narrow section of doma called the kara-usu ba (唐臼場 ‘lever-mortar place’). The ina-beya is also called the niwa-no-oku (庭の奥, ‘niwa rear’) from its location; it is a board-floored area (ita-ma 板間) where harvested rice ears (kari-ho 刈穂) are temporarily piled and straw ‘barrels’ (tawara 俵) full of unpolished rice (genmai 玄米), are stored, among other uses. The daidoko (だいどこ) or ‘dining room’, where the family eats around the firepit (irori 炉), is also called the ojomeya (おじょめや); from the convenience of accessing and communicating with both the doma and the cha-no-ma, it is established between these two spaces.

The interior layouts of the chūmon-zukuri of the Akita Plain (Akita Heiya 秋田平野) developed out of ‘wrapped hiroma’ type (tori-maki hiroma-gata 取巻き広間型) layouts; they are hiroma-type (hiroma-gata 広間型) layouts that resemble regular four-room (seikei yon-madori 整形四間取り) layouts. ‘Upside’ (kami-te 上手) of the doma is the cha-no-ma (茶の間), the ‘gathering room’ (atsumari-heya 集まり部屋) at the centre of everyday life; it is called the chameya (ちゃめや), joi (じょい), or oe (おえ). Behind the ‘head seat’ (kami-za 上座) at the irori is the Buddhist altar (butsudan 仏壇), and above this the gods are enshrined at the kami-dana (神棚). The formal entrance for important guests, with shiki-dai (式台) platform facing the exterior, is called the toriko (とりこ). It seems that in the past/long ago the opening to the toriko was fitted with top-hung, dense-lattice shitomi-do (蔀戸) shutters; this entry is right under the valley (iri-sumi 入隅) of the roof, and in winter could not be used due to the accumulation of snow, so was also called the natsu no guchi (夏の口, ‘summer entry’).

A chūmon-zukuriminka with a hiroma-type (hiroma-gata 広間型) three-room (san-madori 三間取り). Labelled are the stable (umaya うまや), the earth floored utility area (niwa にわ), the hiroma or ‘living room’ (here the cha-no-ma ちゃのま), the formal zashiki (here the dei (でい), and the bedroom (heya へや). Division of the cha-no-ma along the line of the dei - heya partition would result in a would result in a regular four-room layout (seikei yon-madori 整形四間取り) with a front ‘living room’ and rear ‘dining room’ (daidoko だいどこ or cha-no-ma 茶の間).

Behind the butsudan of the chanoma is the master bedroom (fujin-fūfu no shinjo 夫人夫婦の寝所), and up (kami-te ni 上手に) from this are two formal rooms (zashiki 座敷). In double-chūmon plans, an additional small zashiki (ko-zashiki 小座敷) is attached to and projects out in front of these. The zashiki were informally called the dei (でい); in the Tо̄hoku region, where there is a tendency to add -ko to the ends of words, it is called the deikko or deko. The ko-zashiki is called the kojiya (こじや) and was used as a room for young couples, children, etc.; in the houses of the high-status ‘official class’ or ‘executive class’ (kimo-iri-sо̄ 肝煎り層), another entrance might have been added to this ‘upper chūmon’ (kami-chūmon 上中門), used as an entry for government officials (yaku-nin 役人), priests and monks (sо̄bо̄ 僧房), and the like; in the Shо̄nai (庄内) region of Yamagata Prefecture, it is called the zeno-guchi (ぜの口) or the marо̄do (まろうど), from mare-bito no to (稀人の戸, ‘door for visitors from afar’), but in this region it was rare; rather, more importance and emphasis was attached to the toriko entry (toriko-no-guchi とりこの口).

In this region, there are many double-chūmon plans, even amongst relatively small houses; there are examples where the whole roof is of thatch (kusa-yane 草屋根), but often the upper chūmon has a gabled (kiri-tsuma tsukuri 切妻造り) and shingled (kokera-buki 柿葺き) roof, with the beam structure (hari-gumi 梁組) of the gable wall (tsuma-kabe 妻壁) visible for ornamental effect. As this region lies within an oil field (yuden 油田), crude oil (genyu 原油) is applied to the shingles to increase their durability and longevity, a practice called doro-abura-kake or doro-yu-kake (泥油掛け) carried out since the beginning of the Meiji period. The roofs are thickly thatched (kaya-buki 茅葺き); the eaves (noki-saki 軒先) are jettied (segai-tsukuri せがい造り), the roof ridges are clad with either shingles (kokera-buki 柿葺き) or boards (ita-buki 板葺き), with external, ornamental ‘ridge poles’ (ki-mune 木棟, lit. ‘tree ridge’) placed atop them (not to be confused with muna-gi 棟木, the true ridge poles that tie the rafters together at the apex of the roof structure), though occasionally you can also see houses with ridge ‘combs’ (ki-gushi 木ぐし or sen-bon-gata (千本型, lit. ‘thousand tree type’) ridges.

A well-kept single-chūmon minka with deeply ‘carved’ shishi-mado in the facade plane of the chūmon roof and and seemingly copper-clad awning roof over the chūmon entrance.