In the Asahi mountains (Asahi-sanchi 朝日山地) of Yamagata Prefecture can be found a style of minka called taka-happо̄-tsukuri (高はっぽう造り) that is, for Japan, somewhat unusual in its external form.

Along the Rokujūri-goe Highway (Rokujūri-goe Kaidо̄ 六十里越街道) that links the Shо̄nai Plain (Shо̄nai Heiya 圧内平野) and the Yamagata district (Yamagata chihо̄ 山形地方), mountain villages such as О̄ami (大網) and Tamugimata (田麦俣) prospered as bases for pilgrims and ascetics making the journey to Dewa Sanzan (出羽三山). The villagers worked as mountain carrier-guides (gо̄riki 強力) and packhorse riders (mago 馬子), and many also operated travellers’ inns (dо̄sha yado 道者宿) on the side.

In the Meiji period (Meiji jidai 明治時代, 1868 - 1912), the state-mandated separation of Shintо̄ and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri 神仏分離) and the opening of railways saw these villages lose their religious character, and sericulture (yо̄san 養蚕) became their main occupation, with other activities such as forestry and the cultivation of nameko (なめこ Pholiota microspora) mushrooms as supplementary industries, together with small-scale land clearing for agriculture (kaiden 開田, lit. ‘open field’). With the flourishing of export-oriented sericulture, the upper levels within the minka roof space (yane-ura 屋根裏), previously used for travellers’ accommodation, were repurposed into silkworm-raising rooms (san-shitsu 蚕室) and storage spaces. These roof spaces were provided with multiple levels: the floor above the ground floor, i.e. the ‘second floor’ (ni-kai 二階 in Japanese); the second upper level or ‘third floor' (san-kai 三階, called the chishi (ちし) in local dialect; and even a third upper level or ‘fourth floor’ (yon-kai 四階), called the tenjо̄-chishi (天井ちし, ‘ceiling chishi’).

A minka in Arasawa (荒沢) in the watershed of the О̄tori River (О̄tori-kawa 大鳥川), a tributary of the Aka River (Aka-gawa 赤川) that flows across the Shо̄nai Plain (Shо̄nai Heiya 庄内平野). The amaya (あまや), the awning roof over the façade perimeter space (geya 下屋), is tiled here, but examples in the old style have concave (sori 反り) thatched amaya, which together with the main roof and the happо̄ above result in a strange modeling highly reminiscent of a stingray (ei 鱏). Yamagata Prefecture.

In this single-storey ‘long house style’ (yoko-ya tsukuri 横屋造り) example, the happо̄ of the roof space floors (chishi) are at different heights, resulting in a somewhat ‘foreign’ appearance. The part with the eave extension (fuki-oroshi 葺きおろし) on the left is the stable, with a stout sliding door to the livestock entrance; the long lattice visible above the entrance is an aviary (tori-goya 鳥小屋). Yamagata Prefecture.

This house, a two-storey, multi-level ‘long house style’ (yoko-ya tsukuri 横屋造り) minka, was renovated at some point and no longer looks as it does here, but when this picture was taken its roof was the most complex in Tamugimata. As in the previous example, the extended eave (the amaya) gives the house the appearance of being chūmon-zukuri (中門造り) in style; unlike the chūmon-zukuri, however, which is an L-plan form minka where the extension (the chūmon 中門) forms the short leg of the L and as such has its own ridge, in the taka-happо̄-tsukuri the amaya is simply an extension of the main roof plane. Yamagata Prefecture.

One of the takahappо̄-tsukuri minka of Tamugimata in more recent times.

Improvements in methods of rearing silkworms left the light and ventilation provided by the existing hipped roofs (yose-mune-zukuri 寄棟造り) of these minka inadequate, so improvements were also made to the buildings to increase sunlight and air: the gable-end (tsuma-gawa 妻側) roof planes were cut back to produce ‘clipped gable’ (kabuto-zukuri 甲造り, lit. ‘helmet style’) roofs with tall truncated gables, which were provided with distinctive dormer-style windows called taka-happо̄ (高はっぽう ‘high happо̄’); these were also added to the side planes of the roof. With these changes was born the taka-happо̄-tsukuri style so characteristic of minka of this region. The beautiful silhouettes of these roofs with their happо̄ and concave (sori そりor 反り) flares, together with the scissor-shaped ridge ornaments called kuragi-gushi (鞍木ぐし lit. ‘saddle timber comb’) placed on their ridges, give these minka a unique local character.

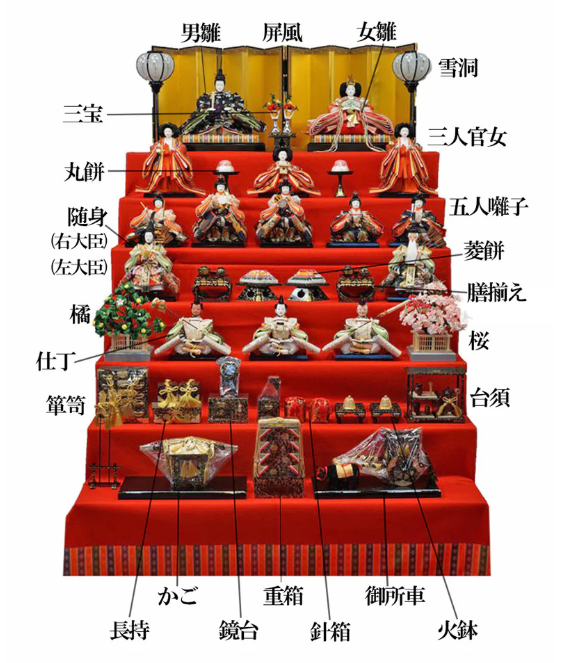

Towards the end of the Meiji period, over half of the village of Tamugimata was lost in a fire, so the style of the houses there can be classified into those based on a single-storey structure (hira-ya-date 平屋建て), built before the fire, and those based on a two-storey structure (ni-kai-date 二階建て), built after it. Additionally, some of the houses are ‘gable entry form’ (tsuma-iri keishiki 妻入り形式) ‘longitudinal house style’ (tate-ya-tsukuri 縦家造り) in their orientation, and some are ‘long side entry form’ (hira-iri keishiki 平入り形式) ‘transverse house style’ or ‘long house style’ (yoko-ya-tsukuri 横家造り). On the ‘doll terrace’ (hina-dan-jо̄ 雛段状) topography of the mountainside, these various designs jostle together as if in competition. They present a remarkable sight, but at present many of these minka have been altered, and it is no longer possible to recall their original appearance.

A ‘doll terrace’ (hina-dan-jо̄ 雛段状)

The village of Tamugimata as it appeared in Shо̄wa 30 (Shо̄wa san-jū-nen 昭和30年), 1956.

A closer view of Tamugimata, 1956.

The internal layouts are of the ‘wrapped hiroma’ type (tori-maki hiroma-gata 取巻き広間型), in the Tо̄hoku pattern (Tо̄hoku-gata): a distribution of rooms such as the o-heya (おへや), de-beya (でべや), and small bedrooms (小寝室) around the hiroma.