The oshi-ita (押板, lit. ‘pushing board’) is an ornamental element of minka, somewhat similar in appearance and function to the more well-known tokonoma (床の間), the formal ‘ornamental alcove’, but distinct from it in several ways, most immediately by its shallowness. The oshi-ita can be found in the Chūbu and Kantо̄ regions, and is commonly seen in particular in the minka of the Tama hills (Tama kyūryо̄ 多摩丘陸) region of Kanagawa Prefecture.

As the etymology suggests, the oshi-ita was originally a simple, unfixed board that sat on the floor near or against the wall, and on which an inkstone (suzuri 硯) or tray (tanzara 短皿) were placed; later by extension it came to refer to the floor board of a tokonoma or ‘study’ (shoin 書院).

There are those of the opinion that the oshi-ita is the precursor of the tokonoma, but Chūji Kawashima is inclined to think that it is of independent origin. In minka, the oshi-ita alcove, only the depth of a post, originally had a religious function and significance: ‘prayer talismans’ (kitо̄-satsu 祈祷札 or o-fuda お札) and ritual vessels (saiki 祭器) were placed in it. Whereas the tokonoma is installed in the formal zashiki, the oshi-ita is is not normally found there, but is located in the ‘living room’ (the hiroma ひろま or dei でい). Within these rooms, it is commonly placed behind the yoko-za (横座), the seating position at the firepit (irori 囲炉裏) furthest from and facing the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間), and adjoining the decorative bedroom entrance (chо̄dai-gamae 帳台構え).

This oshi-ita (押板), on the left, is in its most conventional position: adjoining the formal bedroom entrance (chо̄dai-gamae 帳台構え) on the right, and behind the master’s seat (yoko-za 横座) at the firepit (irori 囲炉裏). Former residence of the Kitamura family (Kitamura-ke 北村家), Kanagawa Prefecture, now relocated to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum (Nihon Minka-en 日本民家園), Kawasaki Prefecture.

In terms of height, the oshi-ita stops at head datum (uchi-nori 内法) height, i.e. the height of the lintels (kamoi 鴨居) of the openings; this is in contrast to the tokonoma, which is slightly taller than the uchi-nori.

In its position at the boundary of the hiroma or dei and the bedroom (nesho 寝所), the oshi-ita normally runs in the direction of the roof beams (hari-yuki hо̄kо̄ 梁行き方向, i.e. transverse to the long axis of the building), as in the Kitamura house above; in the Kiyomiya house below, the bedroom is on the north side of the dwelling, so the partition wall and thus the oshi-ita run in the direction of the wall beams (keta-yuki houkou 桁行き方向, i.e. parallel to the long axis of the building); the latter example is considered to be an old or antiquated style of oshi-ita.

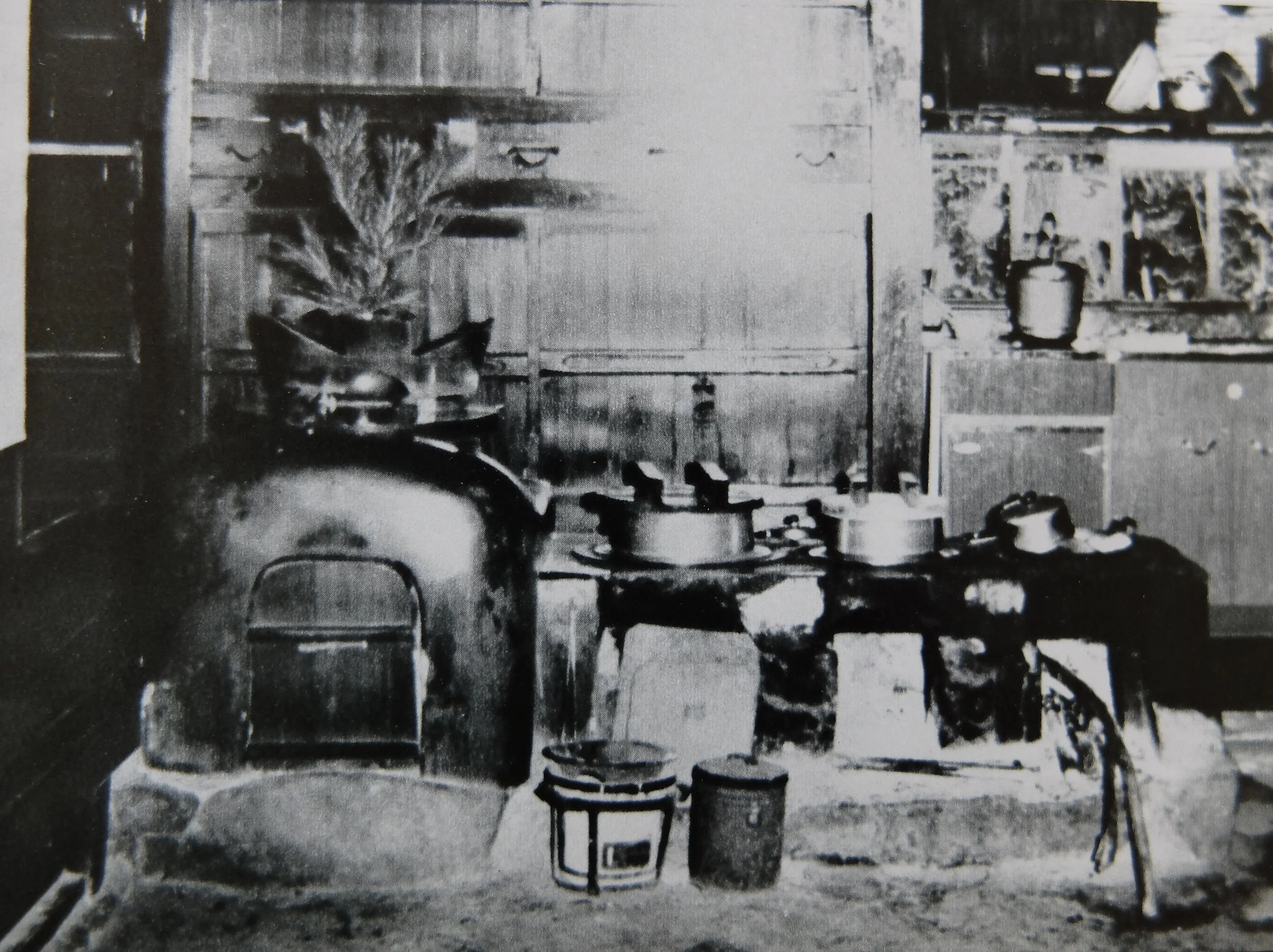

An archetypal and rarely-seen style of south-facing oshi-ita, located ‘up’ from the yoko-za seating position at the firepit (irori). Conventionally, the yoko-za faces the doma, which contains the entrance to the dwelling, to the east; here the doma is largely partitioned off and seemingly obscured from the living area, so a south-facing yoko-za that overlooks the unpartitioned part of the doma-living boundary, where people step up from the doma into the living area, is the most logical ‘surveillance position’.

Adjacent to the oshi-ita, and to the left of the lantern in the image, is the bedroom entrance with timber panelled sliding door(s). The oshi-ita is decorated with a flower vase and Buddhist picture scroll. Former Kiyomiya family (Kiyomiya-ke 清宮家) residence, Kanagawa Prefecture; now relocated to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum (Nihon Minka-en 日本民家園), Kawasaki Prefecture.

Plan of the Kiyomiya house, showing the south-facing oshi-ita (押板) and bedroom entrance to the rear (north) of the irori (炉) in the ‘living room’ (hiroma ひろま), and the earth-floored utility area (dēdoko でえどこ) to the east. Also shown are the lattice partitions (kо̄shi-mado 格子窓) and the ‘step up sill’ (agari-gamachi 上り框) between the hiroma and the dēdoko

Another view of the oshi-ita in the hiroma of the Kiyomiya house, between the entrance to the ‘drawing room’ (dē でえ) to the left and the entrance to the bedroom (ura-beya うらべや) to the right.

The examples below are both from Toyama Prefecture, where the oshi-ita is called the yoroi-tana (鎧棚, lit. ‘armour shelf’) because in the past it was adorned with armour (yoroi 鎧); the small suspended cabinets (tenbukuro todana 天袋戸棚, lit. ‘heaven bag door shelf’) are status signifiers, indicating the dwelling as the residence of a country samurai (gо̄shi 郷士).

The Kitamura family (Kitamura-ke 北村家) residence, Toyama Prefecture (not to be confused with the Kitamura house from Kanagawa Prefecture above). A high-status oshi-ita (押板), with a shelved upper cabinet (ten-bukuro to-dana 天袋戸棚) and full-width shelf (hito-moji dana 一文字棚). Designated an Important Cultural Property.

This example also has a ten-bukuro upper cabinet, but no intermediate shelf. Murakami family (Murakami-ke 村上家) residence, Toyama Prefecture, designated an Important Cultural Property.

The oshi-ita in the image below has a depth somewhat greater than the depth of the posts; in the mountainous areas of the Kantо̄ region there are districts where this type of oshi-ita is known as a kusundoko (九寸床, lit. ‘nine sun toko’). Sun is the Japanese ‘inch’, standardised as 30.303 mm, so 9 sun is around 270mm.

On the right is a relatively deep oshi-ita, known as a kusun-doko. Former residence of the Emuki family (Emuki-ke 江向家), Toyama Prefecture; now relocated to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum (Nihon Minka-en 日本民家園), Kawasaki Prefecture.