The chо̄dai (帳台, lit. ‘curtain platform’), also called mi-chо̄dai (御帳台) and mi-chо̄ (御帳), was an interior element of Heian Period (Heian jidai 平安時代, 794 - 1185) classical architecture. Essentially a ‘room within a room’, it consisted, as the name suggests, of a raised platform (dai 台), laid with tatami mats, with a frame of posts and beams over which were hung curtains (tobari 帳), the whole thing somewhat resembling a room-sized four-poster bed. It functioned as a sitting place and sleeping place in the shinden-zukuri, (寝殿造り, lit. ‘sleep palace construction’), the residences of the ruling Imperial nobility of the period.

An illustration showing an aerial view of a shinden-zukuri (寝殿造り) residence. The main hall, the shinden (寝殿), is at the centre of the complex.

A mi-chо̄dai (御帳台).

An opulent chо̄dai (帳台) on the occasion of the enthronement of an Emperor.

By the time of the shо̄gun-ruled Muromachi period (Muromachi jidai 室町時代, 1333 - 1573), the chо̄dai itself had faded from prominence with the decline of Imperial power, but the name survived in the compound word chо̄dai-gamae (帳台構え), the formal, ornamented ‘doorway’ in a jо̄dan no ma (上段の間, lit. ‘up step space’), a room raised a step above the main floor level in a new style of residential architecture that emerged in the period called shoin-zukuri (書院造り) or buke-zukuri (武家造り, lit. ‘samurai house construction’).

The Tо̄gudо̄ (東求堂) of Jishо̄ Temple (Jishо̄-ji 慈照寺) in Kyо̄to, a surviving example of the shoin style (shoin-zukuri 書院造り).

A jо̄dan no ma (上段の間), raised a step above the level of the main floor, the edge marked with a lacquered interior sill (kamachi 框).

Normally the entry sill (shikii 敷居) of the chо̄dai-gamae is itself raised above the floor level of the jо̄dan no ma, and the entry head is set a step below the main nageshi (長押, head rail) of the room. The opening is furnished with four beautifully decorated opaque sliding doors (fusuma 襖). The gamae of chо̄dai-gamae is pronounced kamae (構え) when read alone, and means ‘structure’, ‘installation’, ‘device’, ‘function’, etc.

The magnificent chо̄dai-gamae (帳台構え) in the Ninomaru Palace Great Hall (Ninomaru Goten О̄-Hiroma 二の丸御殿大広間) in Nijо̄ Castle (Nijо̄-jо̄ 二条城), Kyо̄to.

As is often the case, the name chо̄dai-gamae eventually worked its way down to the vernacular dwellings of commoners; in minka, it refers to a ‘formal’ entry to a dedicated bedroom; it is also sometimes known as nando-gamae (納戸構え). Perhaps the idea of ‘ornamenting’ this part of the minka interior came, like the name chо̄dai-gamae itself, from samurai residences; or perhaps it was an independent and inevitable outcome of the care and sturdiness with which the bedroom partition wall was constructed, motivated initially by the need to protect valuable possessions and the bodies of the inhabitants sleeping within; the fact that this wall faces the living area also makes it an obvious candidate for ‘special treatment’ as a focus of decorative attention in the interior. It should be noted that while the words ‘ornament’ and ‘decoration’ (kazari 飾り) in the Western architectural tradition imply adornment with classical mouldings, sculptural elements, motifs, and so on, in the context of vernacular Japanese architecture, kazari often simply means ‘constructed with finer joinery, higher-quality members, and more of them’. While the chо̄dai-gamae of minka are in no way as opulent as those of the shoin-zukuri, one element of the minka chо̄dai-gamae that has been retained from its aristocratic Muromachi-era progenitor is the raised sill. The head of the minka chо̄dai-gamae, however, is typically at the same height as the nageshi of the room.

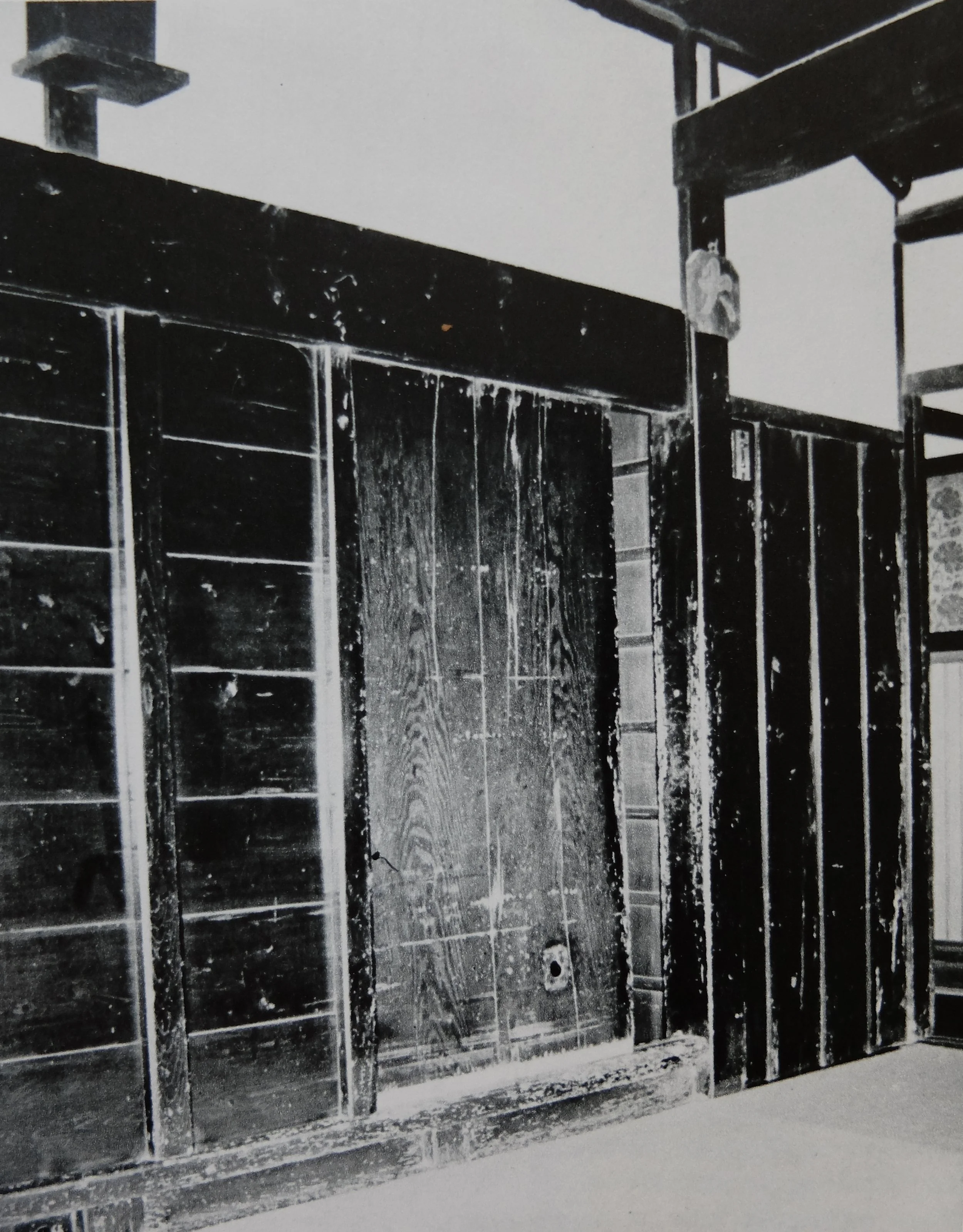

Below is an example of a chо̄dai-gamae in a minka in Kyо̄to. On the side of the bedroom partition that faces the main living areas, called the oe (おえ) and the daidoko (だいどこ), the timber cladding (ita-bame 板羽目) consists of magnificent boards around three centimetres thick, slotted into the bays between closely-spaced posts, reminiscent of the partition wall of the nuri-gome (塗籠) bedroom-storeroom of shinden-zukuri. Here the bedroom wall has developed into something not only sturdy and secure but also attractive.

The construction of the partition wall of the nuri-gome is clearly visible in the lower left of this illustration.

The chо̄dai-gamae in the Yamada family residence, a minka in the Rakuhoku district of Kyо̄to. As in the nuri-gome, horizontal boarrds are slotted into closely spaced posts. The room is secured with a kururu lock; the keyhole and escutcheon for the kururu ‘key’ can be seen in the lower right part of the door. When the door is shut it automatically locks, and cannot be opened from the outside without the key. Kyо̄to City.

The exterior of the bedroom (nando 納戸) of the Imanishi (今西) family residence, an Important Cultural Property, with what is said to be the only remaining chо̄dai-gamae in a townhouse (machiya 町家) in the Kinki region. Above the left half of the high sill is a board-and-stud wall, into or behind which the board door on the right slides. As in the previous example, the kururu keyhole is visible in the lower right part of the door. Nara Prefecture.

Below is the chо̄dai-gamae in a gasshо̄-zukuri (‘praying hands construction’) minka from Etchū Gokayama (越中五箇山) in Toyama Prefecture, with ‘decorative’ cupboards (kazari to-dana 飾り戸棚) on both sides of the entrance. For a farmhouse, this is joinery and construction of the highest class. The room within is ten tatami mats in area; it serves both as the bedroom of the ‘head couple’ (kachо̄ fūfu 家長夫婦, the patriarch of the household and his wife), and as a general storeroom for everything from chests of drawers (tansu 筆笥) and trunks (nagamochi 長持) to grains (koku-rui 穀類). In this region, the room is called the chо̄da (ちょうだ) or chonda (ちょんだ), names that clearly derive from the chо̄dai of the shinden-zukuri. In other areas, such as the Izu Islands (Izu-shotо̄ 伊豆諸島), Tajima (但馬) in Hyо̄go, Shima (志摩) in Mie, Echigo (越後) in Niigata, and Awa (阿波) in Tokushima, the room has retained the name chо̄dai.

The splendidly-constructed chо̄dai-gamae of the Murakami (村上) family residence, designated an Important Cultural Property, in Etchū Gokayama, Toyama Prefecture. The flanking wall next to the sliding door, behind the irori firepit, consists of a single large board called a biwa-ita (琵琶板, ‘lute board’); at left is a shallow decorative alcove, with shelves above, called an oshi-ita (押板).

In the culturally advanced Kinai region, centred around Kyо̄to, Nara and О̄saka, the chо̄dai-gamae disappeared around the middle of the Edo period; even previous to this, many had been converted into ‘regular’ rooms. But from the northern part of Kyо̄to to the Hokuriku region and in cold climate regions like Tо̄hoku, the chо̄dai-gamae remained until relatively recently, unchanged from its old form.