This post will examine ceilings (tenjо̄ 天井) in the formal room (zashiki) and in minka more generally. The main functions of a ceiling are to hide the complex, ‘messy’ structural timbers of the roof space, to ‘formalise’ and provide ornament to the interior, and to prevent the movement of air, thus preserving heat. In extremely basic zashiki in farming and mountain village minka, ceilings are not installed, with the beam structure (hari-gumi 梁組) of the roof space (yane-ura 屋根裏) left exposed, but the typical zashiki is provided with a suspended ceiling (tsuri-tenjо̄ 釣り天井). Rarely, magnificent coffered ceilings (gо̄-tenjо̄ 格天井, ‘lattice ceiling’) can also be found, but zashiki ceilings are normally batten ceilings (sao-buchi tenjо̄ 竿縁天井).

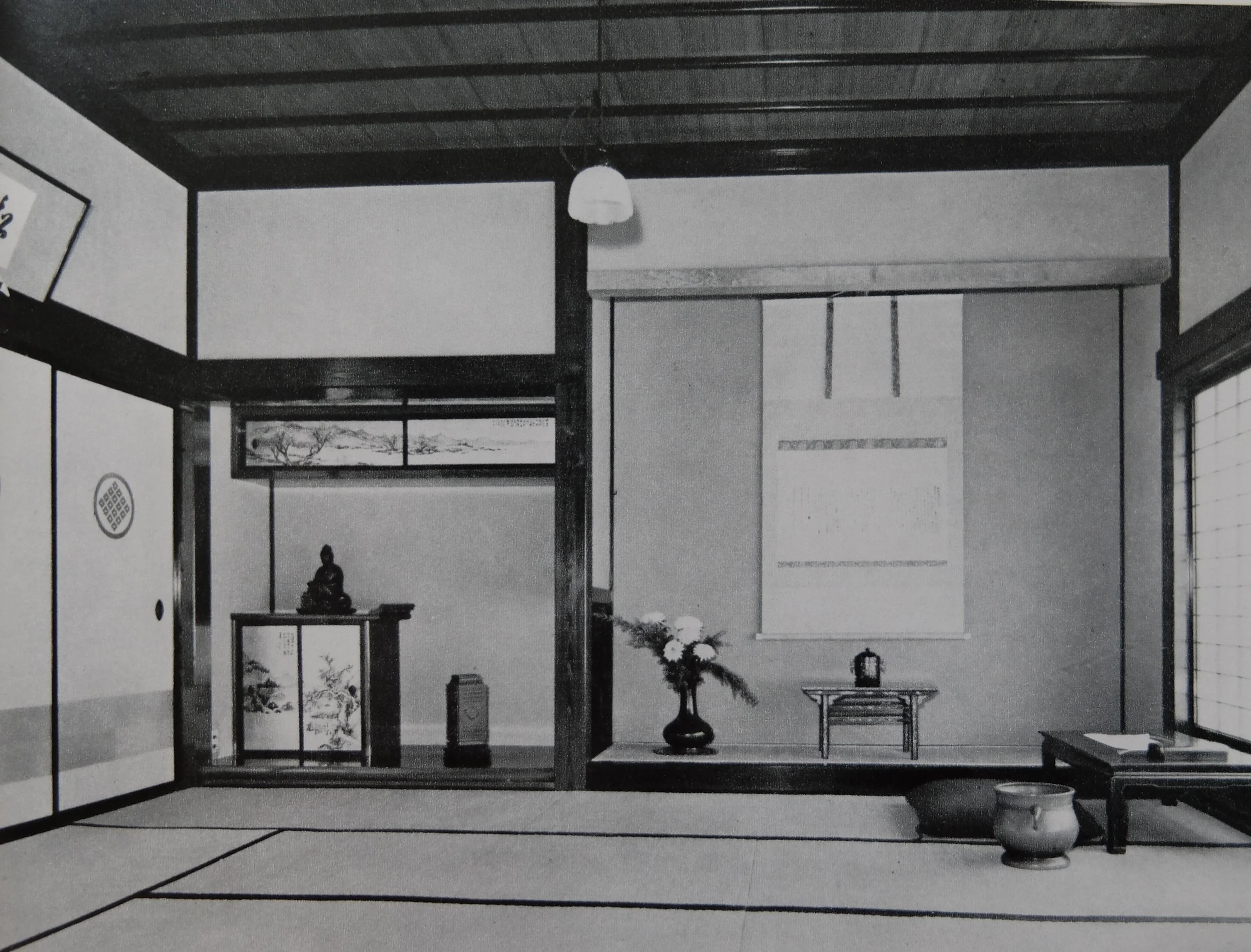

A batten ceiling (sao-buchi tenjо̄ 竿縁天井) in a zashiki. The battens (sao-buchi), as is customary, run parallel to the wall in which the tokonoma is contained, and are spaced at four per ken (間 1.81m), or about 455mm. Isa family (Isa-ke 伊佐家) residence, Kyо̄to Prefecture.

The ceiling battens and ‘cornices’ (mawari-buchi 廻縁) of the batten ceiling (sao-buchi tenjо̄ 竿縁天井) in this ‘high spec’ zashiki, like most of the other timber members visible here, are lacquered (urushi-nuri 漆塗り). Sakurai family (Sakurai-ke 桜井家) residence, Ishikawa Prefecture.

A coffered ceiling (gо̄-tenjо̄ 格天井) installed in a building under construction. Labelled are the ‘lattice battens’ (gо̄-buchi 格縁) and flat-sawn (ita-me 板目) ceiling boards (tenjо̄-ita 天井板).

A carpenter installing ceiling boards (tenjо̄-ita 天井板) over the ceiling battens (sao-buchi 竿縁) in a new ceiling.

In the sao-buchi tenjо̄, slender battens (sao-buchi 竿縁, lit. ‘pole/rod edge’) are suspended from the roof beams via timber hangers (tsuri-ki 釣木, lit. ‘hang timber’), and thin (perhaps only 3mm or so), wide boards of Japanese cedar (sugi 杉, Cryptomeria japonica) or the like are lapped (ha-gasane 羽重ね lit. ‘wing/feather layering’) over the battens and perpendicular to them. The boards are usually lapped by 20mm or so; if thicker boards are used, they may be thinned at the lap.

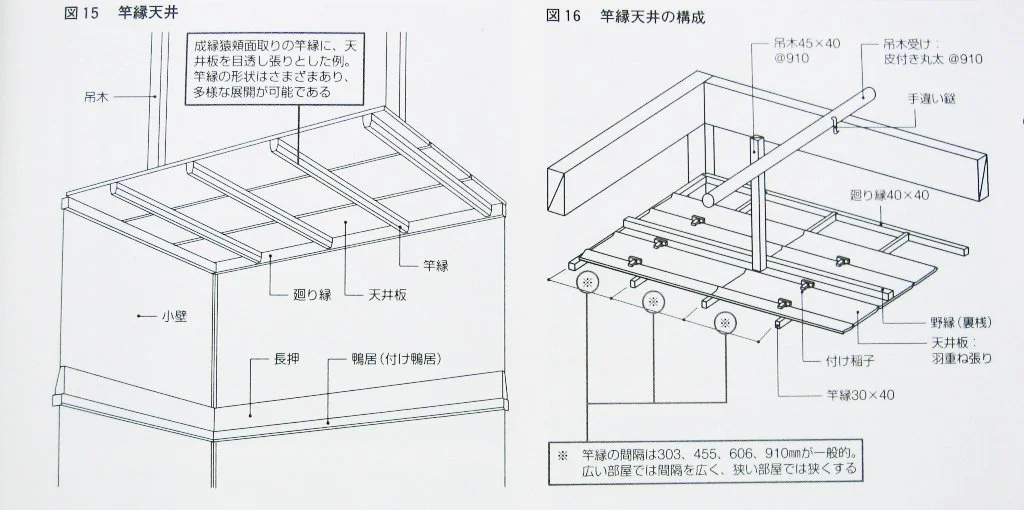

A batten ceiling (sao-buchi tenjо̄ 竿縁天井) illustrated from above and below, showing ceiling boards (tenjо̄-ita 天井板), battens (sao-buchi 竿縁), ‘cornices’ (mawari-buchi 廻り縁), batten hangers (tsuri-ki 吊木 or 釣木), hanger support (tsuri-ki uke 吊木受け), and ‘over battens’ (no-buchi 野縁 or ura-san 裏桟). Common standard pitches for the battens are 303mm, 455mm, 606mm, and 910mm.

Illustration showing various batten (saobuchi さお縁) profiles (keijо̄ 形状) and dimensions (sunpо̄ 寸法). In an example of traditional builders’ understanding of fractal scaling and proportionality in design, dimensions are given not in absolute units but as fractions of the building’s structural post (hashira 柱) dimensions. For example, if the post dimensions were 100mm x 100mm, the batten at top left would be 25mm x 25mm, with 10mm chamfers.

A traditional, labour-intensive method of hanging the battens (sao-buchi さお縁) from the hangers tsuri-ki 釣木), using a type of dovetail joint called yose-ari (寄せあり, lit. ‘draw together ant’) and a peg or wedge (komi-sen 込み栓). The ceiling boards (tenjо̄-ita 天井板) are cut around the joint and the cut is concealed by the batten.

More modern methods of construction: above, the hanger and ‘overbatten’ (no-buchi 野縁) are nailed together; below, the batten (sao-buchi さお縁) is suspended from a wire (tsuri-tessen 釣り鉄線) and screw eye (hiiton ヒートン).

With very thin ceiling boards (tenjо̄-ita 天井板), in this case 3mm, the lap can be formed by simply bending the timber.

Methods used for lapping thicker ceiling boards include: above, thinning a part of one board with a channel so it can be bent over the chamfered edge of the other; and below, inserting the double-bevelled edge of one board into the saw-cut edge of the other.

It is preferred that the sao-buchi run parallel to the wall that the decorative alcove (tokonoma 床の間) is in; the opposite arrangement, when the sao-buchi run perpendicular to the toko wall, is called toko-zashi (床差し, lit. ‘toko facing’) and is strongly disliked. There are not a few toko-zashi ceilings in old minka, however.

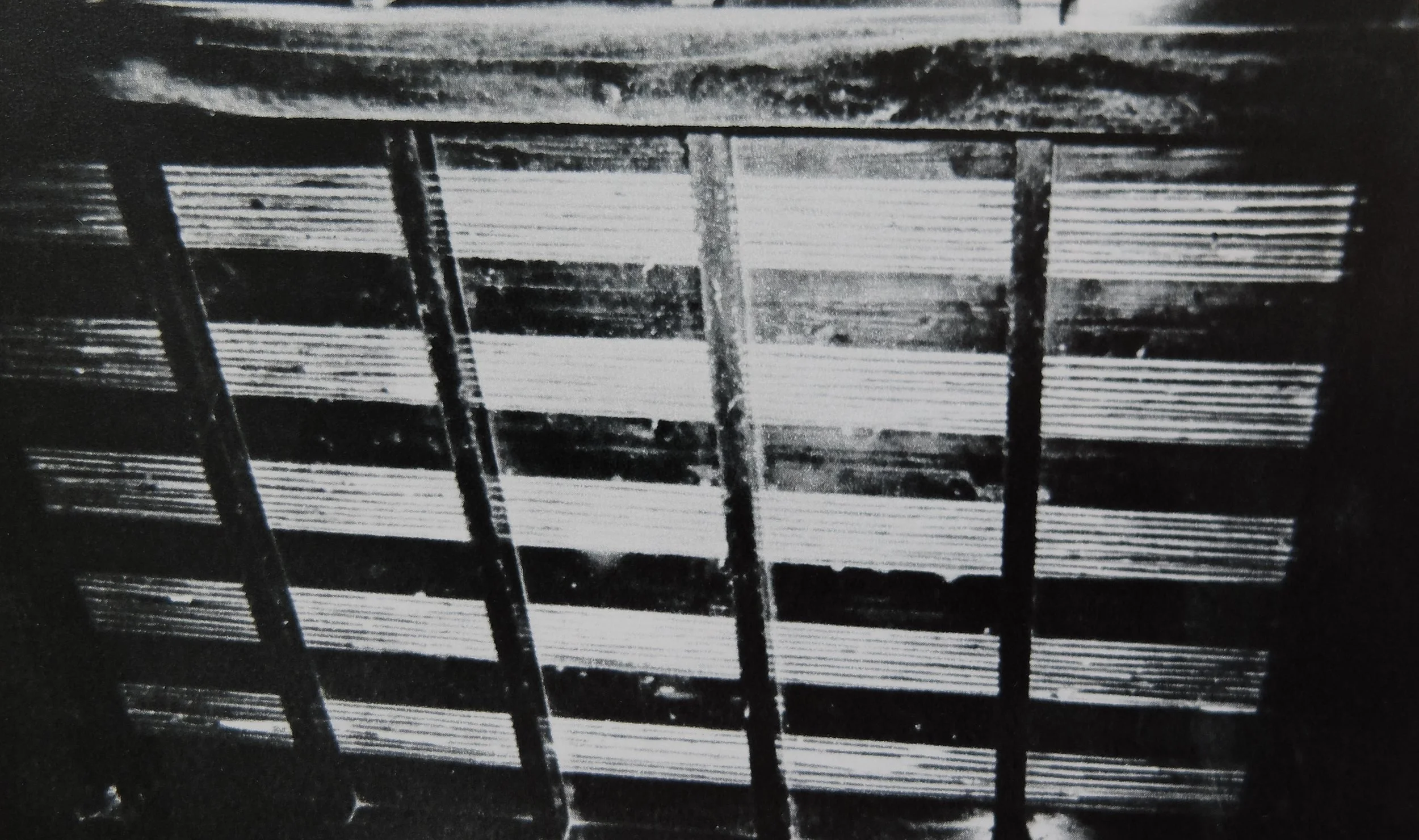

In the unusual kiri-ko tenjо̄ (切り子天井, lit. ‘cut child ceiling’), ceiling boards and permeable screen panels (sunoko 簀の子), usually of bamboo, are used in combination, the aim being to exhaust the smoke from the firepit (irori 囲炉裏). These ceilings are found in minka on the warm-climate Hachijо̄ Island (Hachijо̄ jima 八丈島), south of Tо̄kyо̄. In Japan’s more typical climates, warmer air rising into the roof space not only in itself prevents the room from warming or retaining warmth, but the convection current set up also draws cold air from under the floor and into the room, and so it is said that one should aim for as airtight a ceiling as possible. In a zashiki with such a ceiling, only charcoal would be used for a fire.

This ceiling, from a minka on Hachijо̄ Island (Hachijо̄ jima 八丈島), is a type of batten ceiling (sao-buchi tenjо̄ 竿縁天井) that combines sections of the typical board (tenjо̄-ita 天井板) and batten construction with sections of screen (sunoko 簀の子) and batten construction, as seen here. This type of ceiling is known as kiri-ko tenjо̄ (切り子天井). Okiyama family (Okiyama-ke 沖山家) residence, Tо̄kyо̄ Prefecture.

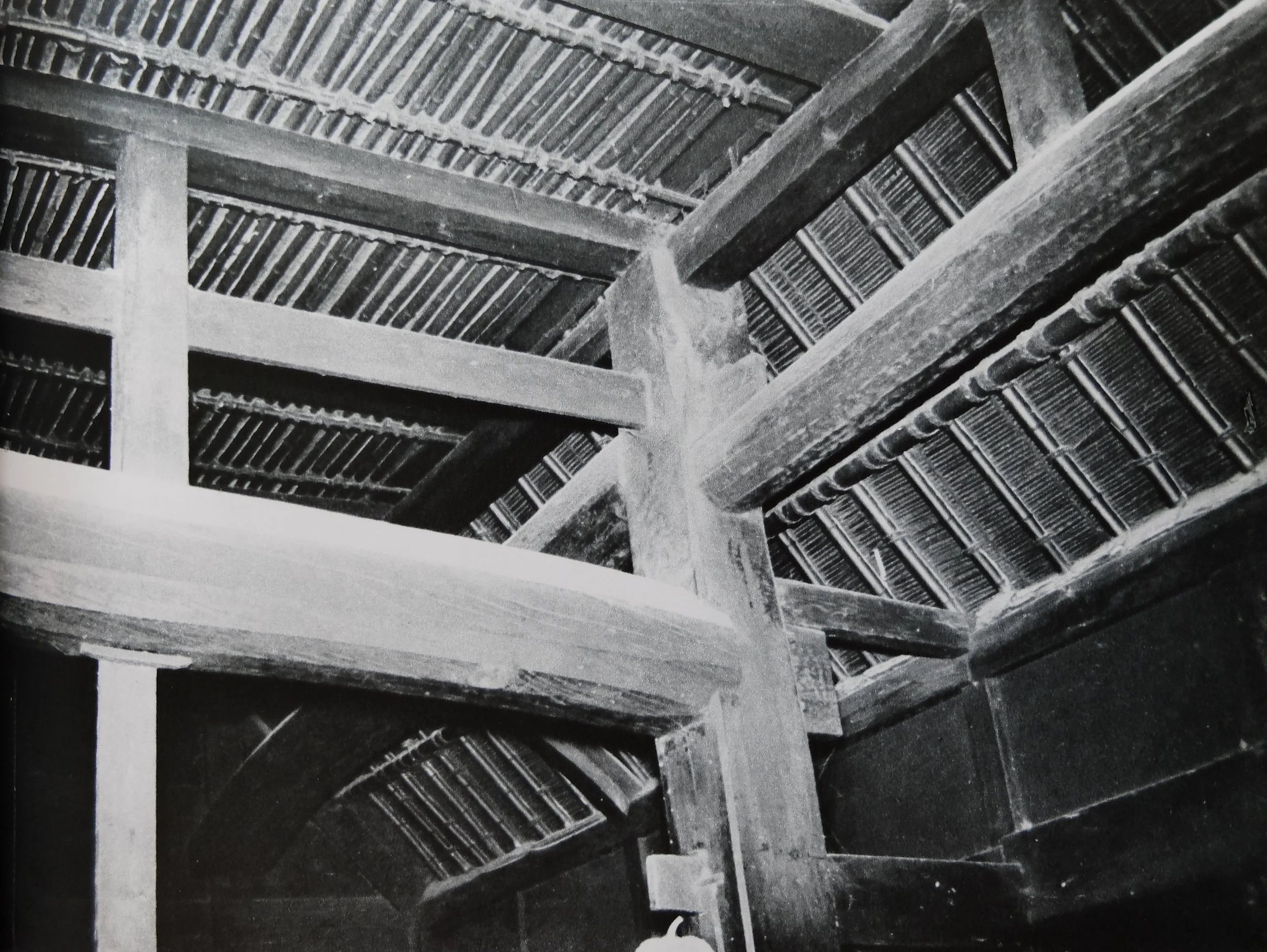

Zashiki ceilings, as seen in in the images included here, are almost always sao-buchi tenjо̄, but if an enclosed ‘verandah’ (engawa 縁側) is associated with the zashiki, its roof structure is often left exposed. As the engawa is at the building perimeter in the ‘eave space’ (geya 下屋) beyond the exterior wall plane, the roof structure here typically only consists of rafters (taruki 垂木) and so is neater in appearance than the more complex roof structure over the main jо̄ya (上屋) space of the building where the zashiki is located. Later-period tile-clad (kawara-buki 瓦葺き) or board-clad (ita-buki 板葺き) roofs’ under-eave structures consisted of rafters, sub-roof boards (noji-ita 野地板), tile battens (kawara-zan 瓦桟 or komai 小舞) and anti-ponding boards (hiro-komai 広小舞); when left visible, these members were all finished with a plane (kanna 鉋), and good quality timber, free of knots, cracks or other defects, was used for noji-ita, improving their presentability. These ‘beautified’ noji-ita are called keshо̄ noji-ita (化粧野地板), and such roofs are called keshо̄ yane-ura (化粧屋根裏, lit. ‘cosmetic roof underside’). In thatched roofs (kusa-yane 草屋根, lit. ‘grass roof’) too, when the underside of the roof is left visible, reed screens (yoshizu 葭簀) or the like function as the keshо̄-noji (化粧野地, ‘cosmetic subroof’): they are laid on the rafters, with the thatch laid over them.

The enclosed geya space ‘verandah’ (engawa 縁側) of this building boasts a fine keshо̄ yane-ura (化粧屋根裏, lit. ‘cosmetic roof underside’) with very high quality defect-free rafters (taruki 垂木) and cosmetic sub-roof boards (keshо̄ noji-ita 化粧野地板).

In rooms in which the tea ceremony (茶席 chaseki) is conducted, there may be a desire to emphasise the design of the geya roof structure as a point of appreciation and conversation, so the keshо̄ yane-ura of the geya is incorporated into the room as an interior compositional element, resulting in what is called a kake-komi tenjо̄ (掛込み天井, lit. ‘bring in ceiling’): a ceiling that combines a flat section (hira tenjо̄ 平天井) and a sloped or ‘lean-to’ section (kata-nagare tenjо̄ 片流れ天井); the sloped section of ceiling may be over the genuine perimeter geya space of the structure, or it may be ‘faked’, within the interior jо̄ya space, or even in a modern apartment.

The rear of this tea-room (cha-shitsu 茶室) features a kake-komi tenjо̄ (掛込み天井) that incorporates (or imitates) the geya space roof.

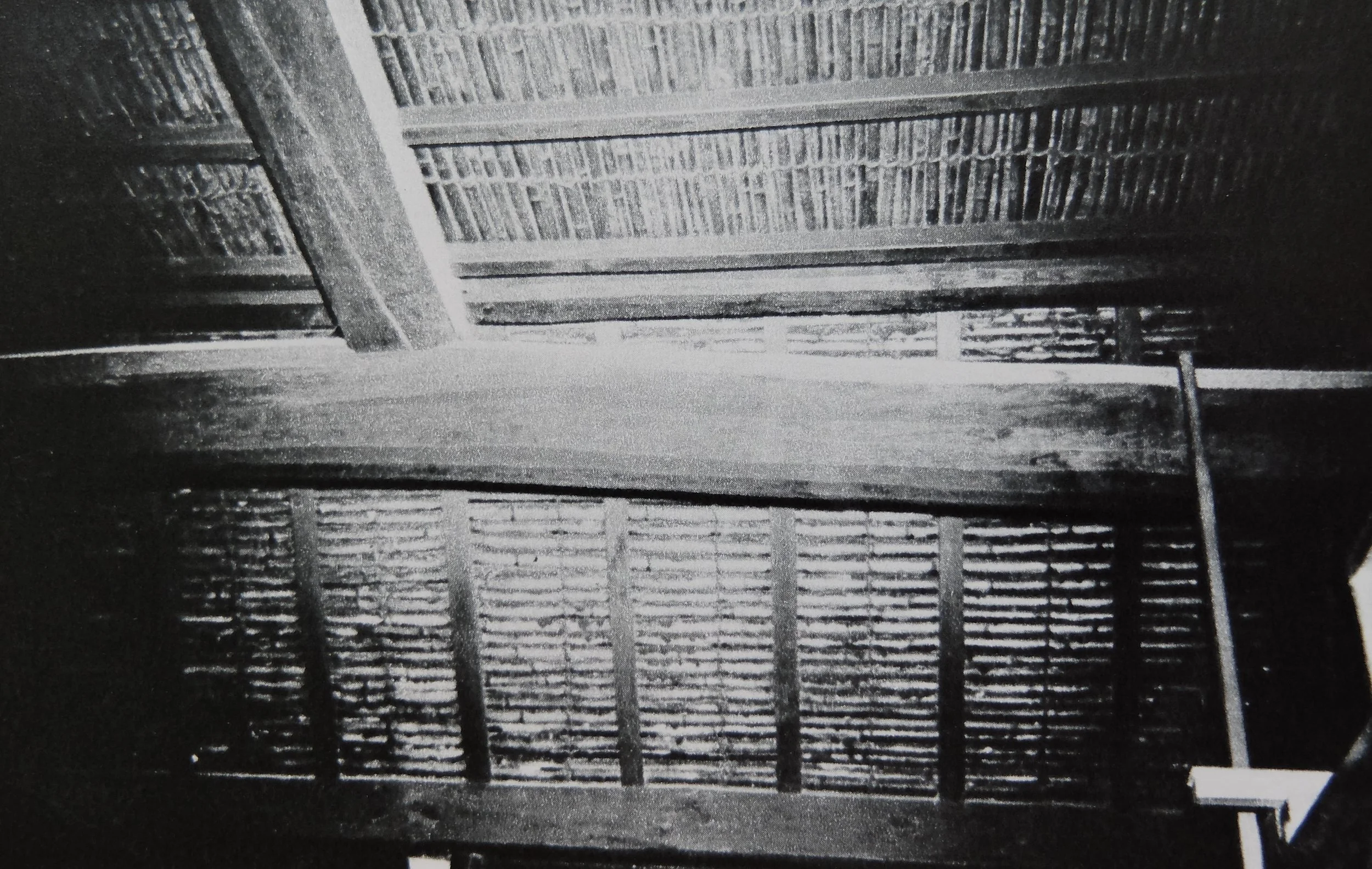

As for ceilings over areas other than the zashiki, often the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間) of minka had a ‘cosmetic roof space’ (keshо̄ koyaura 化粧小屋裏), such as bamboo screens (takesu 竹簀) laid over the beams, to form what is known as a takesu tenjо̄ (竹簀天井, ‘bamboo screen ceiling’). This allowed smoke from the stove (kamado 釜土) or irori (囲炉裏) to rise freely up into the roof space (koya-ura 小屋裏). In Kansai (western Honshū) minka, the kamado was built in a separate part of the doma called the kama-ya (釜屋), and only the ceiling above this part was made permeable; the ceiling over the rest of the doma was airtight. With a ceiling of takesu alone, air flow is excessive, so the upper side of the takesu can be plastered over with clay or earth (tsuchi 土); such a ceiling is called yamato tenjо̄ (大和天井). Yamato tenjо̄ are not used in zashiki, but may be found above the semi-formal dei (でい) and the dining room/kitchen (daidokoro だいどころ or daidoko だいどこ). Alternatively, if the space above the dei or daidoko is used as a kind of attic floor known as tsushi ni-kai (厨子二階), the underside of that floor serves as the ceiling for those spaces below. This type of ceiling is called a neda tenjо̄ (根太天井 ‘joist ceiling’), hari tenjо̄ (梁天井 ‘beam ceiling’), or chikara tenjо̄ (力天井, ‘strength ceiling’). Such ceilings are considered utilitarian (shita-mawari 下回り), in contrast to the formal sao-buchi tenjо̄ of the zashiki.

The main ceiling in this image is a bamboo screen ceiling (sunoko tenjо̄ 簀の子天井), spread on its upper side with a floor of matting (mushiro 莚). The sloped ‘descending ceiling’ (kudari tenjо̄ 下り天井) over the eave space (geya 下屋) is a ‘cosmetic under-roof’ (keshо̄ koya-ura 化粧小屋裏) consisting of reed screens (yoshizu 葭簀) laid over bamboo rafters (taruki 垂木 or 棰). Nomura family (Nomura-ke 野村家) residence, Shiga Prefecture.

In this type of bamboo screen ceiling (sunoko tenjо̄ 簀の子天井) known as yamato tenjо̄ (大和天井), the upper side of the screen is plastered with clay. Yamato tenjо̄ are often used above the earth-floored utility area (doma 土間) and above the non-formal gathering or ‘living’ rooms of the dwelling. Hirai family (Hirai-ke 平井家), Shiga Prefecture.