The akari-shо̄ji, the paper-covered timber lattice sliding partition introduced in last week’s post, is arguably more representative and expressive of the aesthetic of Japanese architecture than any other architectural element.

Akari-shо̄ji used in the main opening and above the transom, demonstrating the dappling and shadow effects characteristic of shо̄ji, not possible with glazed windows.

Today generally just called shо̄ji, the akari-shо̄ji did not appear primarily for aesthetic reasons, however. In practical terms, it functions to obstruct wind and drafts but permit the passage of light, and the precision of its joinery means that it can be opened and closed with a light touch while also being reasonably robust. Its great weakness, however, is its vulnerability to rain and water.

It is thought that the earliest shо̄ji developed out of the shitomi (蔀) or shitomi-do (蔀戸), external wall fittings that date back to the Heian period or earlier and were the principal opening devices of the Buddhist temples and shinden (神殿) residences of that time. Shitomi are characteristically top-hung, and generally present as a fine square lattice that is either ‘blind’ (backed with thin timber boards) or hung with paper.

Illustration showing ha-jitomi (半蔀).

Paper-covered ha-jitomi (半蔀) on a Buddhist temple. The upper panels are top-hung and suspended from iron hooks that hang down from the eave rafters.

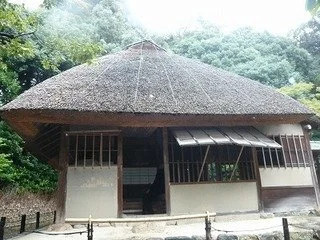

Primitive strut-propped board shitomi in a warm-climate minka.

In particular, the ha-jitomi (半蔀, ‘half shitomi’), consisting of a top-hung and outwards-opening upper lattice shutter and a lower removeable lattice panel, evolved into the koshi-daka shо̄ji (腰高障子 lit. ‘waist high shо̄ji’), with an upper half of papered akari-shо̄ji and a lower half of solid board (itado 板戸), which was widespread before the development of sliding storm shutters (amado 雨戸 ‘rain door’) from the later Edo period. The papered upper half of the koshi-daka shо̄ji is protected from the weather by the deep eaves typically found on traditional Japanese buildings.

A pair of painted koshi-daka shо̄ji (腰高障子) from the Azuchi-Momoyama period (Azuchi-Momoyama jidai 安土桃山時代 , 1573 - 1603).

After the introduction of amado, ‘low-waisted’ shо̄ji resembling the modern type and ‘waistless’ shо̄ji called mizu-shо̄ji (水障子, ‘water shо̄ji), mizu-goshi shо̄ji (水腰障子, ‘water waist shо̄ji’) or koshi-nashi shо̄ji (腰無障子, ‘waistless shо̄ji’) appeared, in a rich variety of designs.

Sliding storm shutters (amado 雨戸) protect the akari-shо̄ji in this minka.

It the era before glass, the paper of shо̄ji in external walls could be further protected against rain with a finish of tung oil (kiri-abura 桐油); these oil paper (abura-gami 油紙) shо̄ji were called ‘oil shо̄ji’ (abura shо̄ji 油障子). In snowy regions, in preparation against high snowfall, there are shо̄ji with extremely high waists, and fittings that are perhaps better categorised as ‘lantern storm shutters’ than shо̄ji, called ame-shо̄ji (雨障子, ‘rain shо̄ji) or yamato-shо̄ji (大和障子).

Illustration of a generic ‘waisted’ (koshi-zuke 腰付け) akari-shо̄ji with the parts labelled: top rail (kami-zan 上桟), lattice ‘muntins’ (kumiko 組子), stiles (kamachi 框), mid-rail (naka-zan 中桟), ‘waist board’ (koshi-ita 腰板), and bottom rail (shimo-zan 下桟).

Illustration of some of the common variants of the basic shо̄ji. Top row: koshi-zuke tate-shige yoko-bitai iri (腰付縦しげ横額入り, lit. ‘waisted vertical frequent horizontal picture-frame inserted’); koshi-zuke ara-gumi о̄-bitai iri (腰付荒組大額入り, lit. ‘waisted rough grid big picture-frame inserted’); mizu-koshi ara-gumi yuki-mi (水腰粗組雪見, lit. ‘water waisted rough grid snow view’). Bottom row: koshi-zuke yoko-shige bitai iri (腰付横しげ額入り, lit. ‘waisted horizontal frequent picture-frame inserted’); mizu-koshi ara-gumi mu-chi (水腰粗組無地, lit. ‘water waisted rough grid no ground’); koshi-zuke yoko-shige neko-ma (腰付横しげ猫間, lit. ‘waisted horizontal frequent cat space’).

Mizu-shо̄ji (水障子) with no ‘waist board’ (koshi-ita 腰板), only a bottom rail (shimo-zan 下桟), so the paper and lattice (kumiko 組子) extend almost to the floor.

The introduction of glass saw the development of shо̄ji with a papered upper half and glazed lower half, called yuki-mi shо̄ji (雪見障子, ‘snow viewing shо̄ji’), and neko-ma shо̄ji (猫間障子, ‘cat space shо̄ji’), with operable papered panels that can be slid aside to reveal or hide the glazing and the view as desired. Cats are notorious for destroying shо̄ji paper, and the neko-ma name and design might come from a motivation to reduce this likelihood by providing them with a view out.

Yuki-mi shо̄ji (雪見障子) in the end wall of a relatively modern dwelling

The top of the shо̄ji and other types of sliding partition run in grooves cut into the opening head (kamoi 鴨居); in zashiki, there is typically a picture rail or ‘frieze rail’ (nageshi 長押) above the kamoi, but in minka the nageshi might be omitted, and instead a deep lintel beam (sashi-gamoi 差鴨居), with grooved soffit, serves both functionally, to hold the sliding partitions, and visually, as a kind of picture rail.

Even in minka of the higher classes there are examples, as here, where a ‘frieze rail’ (nageshi 長押) is not present, and a deep, grooved lintel beam (sashi-gamoi 差鴨居) is used instead. The transom panels (ranma 欄間) between the rooms are magnificent ‘through-carved’ (tо̄shi-bori 透し彫り) ‘board ranma’ (ita-ranma 板欄間), while between the far room and the external verandah (en 縁) there are sliding shо̄ji panels. The opaque fusuma (襖) partitions are painted in the ‘flower-and-bird picture’ (kachо̄-zu 花鳥図) genre by a famous artist. О̄kaku family (О̄sumi-ke 大角家) residence, Shiga Prefecture, an Important Cultural Property. 東海道 の本陣 梅の木 茶屋是斉屋

Conventionally there are transom panels (ranma 欄間) between the nageshi and the ceiling; in the partition walls between rooms, this is normally a carved ita-ranma. In regional areas you can find many interesting ranma carved with rustic, bold designs; but in the strictly formal ‘palace style’ (goten-fū 御殿風), ranma panels of very finely spaced vertical timber members called osa-ranma (筬欄間, lit. ‘reed ranma’), hanazama (花狹間, lit. ‘flower narrow space’), and take-no-fushi ranma (竹の節欄間 lit. ‘bamboo node ranma’) are used.

Two styles of ranma are used in this space: on the left, an elaborately-carved ita-ranma (板欄間); on the right, a fine lattice osa-ranma (筬欄間).

In the transom between the zashiki and the ‘verandah’ engawa, there is normally a papered lattice sliding shо̄ji panels, but in more ‘stylish’ or fashionable 洒落た zashiki, ‘comb-shaped’ ranma (kushi-kata ranma 櫛形欄間) and ‘corner cut’ ranma (sumi-kiri ranma 隅切欄間) shitaji-mado (下地窓, a window formed by omitting the plaster from part of the wall, leaving the lath exposed, and without a surrounding timber frame) can be found, perhaps covered with a ‘hanging shо̄ji’ (kake-shо̄ji 掛障子).

A ‘comb-shaped’ ranma (kushi-kata ranma 櫛形欄間), with two sliding shо̄ji panels covering the shita-ji mado opening.

A ‘corner cut’ ranma (sumi-kiri ranma 隅切欄間), with two sliding shо̄ji panels covering the shita-ji mado opening. The main opening consists of four yuki-mi shо̄ji.

The silhouette of a ‘flame window’ (katо̄-mado 火灯窓) viewed through closed akari-shо̄ji.

A removeable kake-shо̄ji (掛障子, ‘hanging shо̄ji), used on smaller windows such as shitaji mado. It is suspended by its ‘horns’ (tsuno 角) on two hooks and restrained at the bottom by a third centre hook.