The Nara basin (Nara bonchi 奈良盆地), and the ancient district of Yamato (大和), in present-day Nara Prefecture, has long been a fertile ground from which Japanese culture has spread. Its forms of habitation, too, are unique in various ways, and include the settlements known as kaito (垣内, lit. ‘fence inside’), the ‘closed grounds/site’ (heisa-teki-na yashiki 閉鎖的な屋敷) arrangement called kakoi-tsukuri (囲い造り, ‘enclosed style’), and the singular gable-roofed (kiri-zuma yane 切妻屋根) style of house called takahe-tsukuri (高塀造り, ‘high wall style’). These forms arose because the settlements of the Nara Basin, more than simply being farming villages, were characterised by each being like its own city-state (toshi-kokka 都市国家). The unique site organisation (yashiki-gamae 屋敷構え) was constrained and determined by the jо̄ri-sei (条里制) system of land subdivision, used in Japan from the 8th to the late 15th century, and the gable-roof construction (kiri-tsuma tsukuri 切妻造り) with white-plastered (nuri-gome 塗籠) gable ends (tsuma-gawa 妻側), reminiscent of urban dwellings, are thought to have developed out of this fact.

In the ‘enclosed style’ (kakoi-tsukuri 囲い造り), as seen in below, a south-facing main building (omo-ya 主屋) is built in the large courtyard garden (naka-niwa 中庭, ‘inner garden’), and the perimeter of the ‘lot’ (yashiki 屋敷) is enclosed with auxiliary structures (fuzoku-ya 付属家) such as the gatehouse (nagaya-mon 長屋門), storage buildings (naya 納屋), plastered storehouse (dogura 土蔵), and earthen walls (dobei 土塀). There are almost no openings in this exterior, outwards-facing perimeter; light and ventilation are obtained from the inner, courtyard-facing side, in a ‘courtyard house’ style arrangement that was a response to the disordered and insecure social conditions of the middle ages.

In a village in the Nara basin, two adjacent kakoi-tsukuri (囲い造り, ‘enclosure style’) minka viewed from the west, the one in the foreground mostly obscuring the one behind it, except for its higher omo-ya. The perimeters of the sites are enclosed with auxiliary buildings and earth walls. Within each perimeter there is a large ‘dry garden’ (hi-niwa or kantei 干庭) for light and ventilation. Nara City (Nara-shi 奈良市), Nishi no Kyо̄ (西の京), Nara Prefecture.

These settlements are themselves called ‘moated kaito’ (kangо̄-kaito 環濠併内), with the villages’ perimeters ringed by moats (hori 濠); many villages were concealed with earth walls (dobei 土塀) and bamboo thickets (take-yabu 竹薮), and the streets or roads within them were laid out in T-intersections (T-gata T型) and swastika-shape (manji-gata 卍字型) intersections, giving the appearance of a maze, and preventing easy infiltration by outsiders. Various factors are put forward in explanation of the strongly defensive character displayed by these settlements, including the suppression of the Ikkо̄ sect (Ikkо̄-shū 一向宗) by Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) in the late 16th century, and violence perpetrated against the local people by the warrior monks (sо̄hei 僧兵) of the Seven Great Temples of Nara (Nanto Shichi-Daiji 南都七大寺) since ancient times; suffice it to say that the farmers of Yamato, where Samurai were not permitted to enter, had no option but to take the preservation of their lives into their own hands.

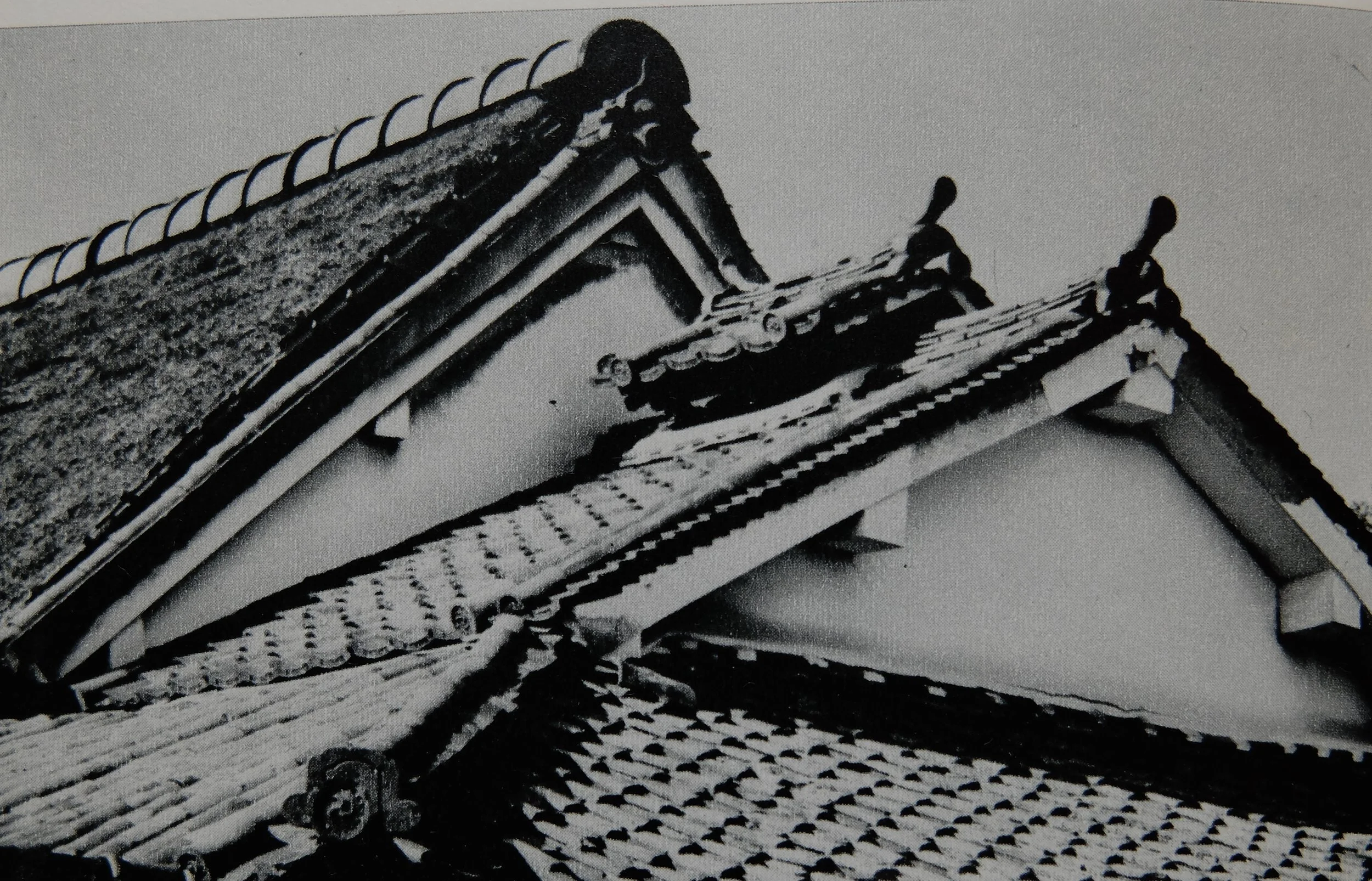

The takahe-tsukuri style is one which combines a thatched (kusa-buki 草葺き) main volume (omo-ya 主屋), which is the raised-floor (taka-yuka 高床), habitable part (kyojū-bu 居住部) of the dwelling, and a tiled (kawara-buki 瓦葺き) ‘stove house’ (kama-ya 釜屋), which is the earth-floored part (doma-bu 土間部); between them is a white-plastered firewall (bо̄ka-heki 防火壁) that rises exceptionally high, hence takahe (高塀 ‘high wall’). The beauty of the composition — the acute-angled takahe that divides the omo-ya off from the kama-ya; the contrast of the thatch of the omo-ya with the tiles of the lower roof (ochi-mune 落棟) of the kama-ya and of the lean-to roofs over the perimeter spaces (geya 下屋) of the omo-ya; the juxtaposition of steep and shallow roof pitches; and the weaving together of materiality and colour of the tile, thatch, and the chalk-white (hakua 白亜) of the takahe — justifies the claim that the takahe-tsukuri stands at the apex of all minka styles.

A variant style of takahe-tsukuri known as hizumi-takahe (ひずみ高塀), in which the ridge of the omo-ya (the omo-mune or shutо̄ 主棟, ‘main ridge’) is higher even than the takahe. The lower ridge (ochi-mune 落棟) of the kama-ya normally has a ‘smoke exhaust tower’ (kemuri-dashi yagura 煙出し櫓), as here. It is common in Kawachi for the omo-mune to have such large capping tiles о̄-ganburi-gawara (大雁振瓦), but this example in Yamato is unusual. Shiki County (Shiki-gun 磯城郡), Nara Prefecture.

The style was originally restricted to the minka of the upper-classes and those of high-status, but from the final years of the Edo period (bakumatsu 幕末, 1853 - 1868), with the improvement in the economic position of farmers brought about by cotton and rapeseed oil production, and the abolition of the class system (mibun-sei 身分制), the style gradually became common, to the point where it could eventually be found everywhere across the Nara basin.

This style of minka has also been called Yamato-mune zukuri (大和棟造り, ‘Yamato ridge style’), but this seems to be a name used by scholars from Tо̄kyо̄; it is not in fact clear whether the prototype form (genkei 原型) of the takahe-tsukuri originally arose in Yamato, or in the old Kawachi Province (Kawachi no Kuni 河内国), present-day eastern О̄saka Prefecture. It is also found in the Settsu (摂津, present-day central and northern О̄saka Prefecture) and Izumi (和泉, present-day south-western О̄saka) districts, but the takahe-tsukuri minka in these areas are thought to have propagated from Yamato and Kawachi.

Takahe-tsukuri minka are also widely found in the Sekkasen (摂河泉) area of О̄saka Prefecture. The takahe of Kawachi takahe-tsukuri are characterised by having a relatively wide takahe, a ‘water cutting eave’ (mizu-kiri hisashi 水切庇) attached to the gable (tsuma 妻), and a tiled upper section to the omo-ya roof. О̄saka Prefecture.

In the takahe-tsukuri of the Nara Basin, roof tiles called tome-buta-gawara (留蓋瓦, ‘stay lid tile’), ornamented with doves, are placed either singly or in pairs on the apexes of the tiled takahe ridges, and form part of the local scenery.

Tome-buta-gawara (留蓋瓦) ridge tiles, ornamented with doves, adorn the apexes of the takahe at each end of the omo-ya of this takahe-tsukuri minka.

The majority of takahe-tsukuri have regular four-room layouts (seikei yon-madori 整形四間取り), but among smaller-scale houses and precursor examples, front-zashiki three-room layouts (mae-zashiki san-madori 前座敷三間取り) can also be seen.