Old minka were generally single-storey; in fact, dwellings with more than a single ‘formal’ or ‘inhabitable’ level were essentially proscribed to commoners until the end of the Edo period, and buildings of three stories* or more were extremely rare. The utilitarian roof spaces of minka were therefore not generally accessed via anything substantial enough to warrant the title ‘stairs’ (kaidan 階段, lit. ‘grade/level + step/stair’): the devices used to access storage areas (mono-oki 物置) or sericulture ‘rooms’ (san-shitsu 蚕室, lit. ‘silkworm room’) in the roof space were basically ladders (hashigo 梯子), though constructed with somewhat more care and with a slightly more robust frame (kigara 木柄) than usual. These were called hashigo-dan (梯子段 ‘ladder step/stair), dan-bashigo (段梯子 ‘step/stair ladder)’, or saru-bashigo (猿梯子 ‘monkey ladder’).

The upper ‘grating floors’ (ama あま) under the steeply-pitched roof of this gasshо̄-zukuri (合掌造り ‘praying hands style’) minka are accessed by ‘monkey ladders’ (saru-bashigo 猿梯子); fixtures of this standard are common in ‘regular’ minka. The ‘ladders’ have flat treads rather than round rungs, and are lashed with rope to stop them from slipping. Murakami family (Murakami-ke 村上家) residence, Toyama Prefecture.

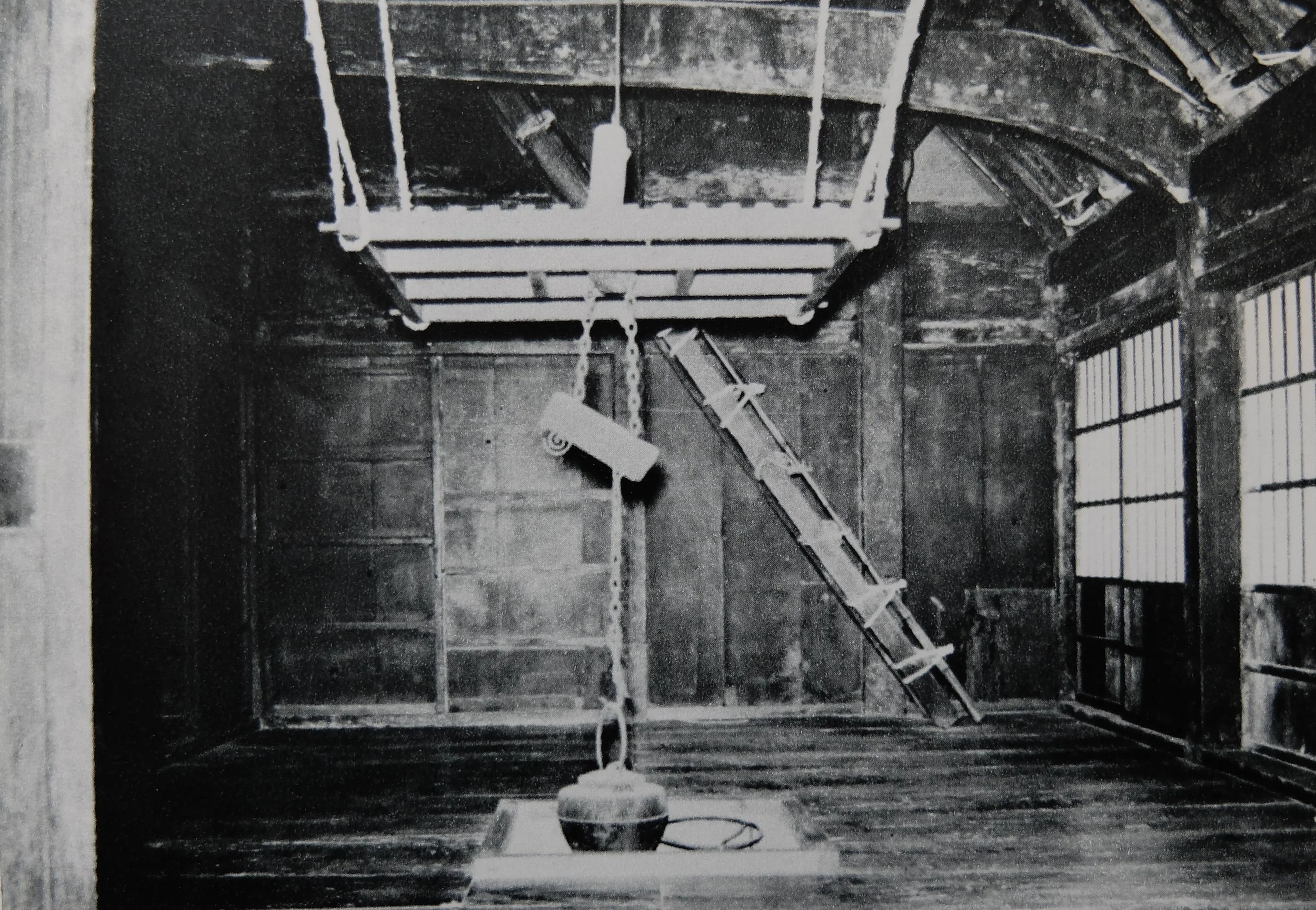

A somewhat more advanced example of the ‘monkey ladder’ than that shown in the previous image. The stair is wider, and a bamboo handrail (te-suri 手摺り) has been added. Emukai family (Emukai-ke 江向家) residence, formerly Toyama Prefecture, now relocated to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum, Kawasaki City.

In townhouses (machiya 町家) and inns (hatago-ya 旅籠屋) on major road routes (kaidо̄-suji 街道筋), because of the necessity of having habitable rooms on the upper storey (nikai 二階), there was some progress in the design of the hashigo-dan: it was improved by making its gradient shallower, and increasing the depth of the tread boards (fumi-ita 踏板).

So that the feet of those using the stairs would not be visible from below, ‘back boards’ or ‘backing boards’ (ura-ita 裏板, lit. ‘rear board’) were attached to the underside of the stair, and consideration might also be given to children and the elderly by adding a handrail (te-suri 手摺, lit. ‘hand rub’). The boards (ita 板) of the steps (fumi-dan 踏段) are also called dan-ita (段板); they are supported on each side by thick board stringers, called gawa-geta (側桁 ‘side beam’) or sasara-geta (簓桁 ‘bamboo whisk beam’); this style of stair is called fumi-ita kaidan (踏板階段, ‘tread stair’) or hako-kaidan (箱階段, ‘box stair’). The style of stair in which individual vertical riser boards (ke-komi ita 蹴込板, lit. ‘kick in board’) are fitted between each space between the treads, rather than the ura-ita which run the full length of the stair, is called ke-komi ita kaidan (蹴込板階段 ‘riser stair’).

Section of a typical ‘riser stair’ (ke-komi ita kaidan 蹴込板階段) with the various components labelled: stringer (sasara-ita ささら板), ‘tread board’ (fumi-ita 踏み板), effective tread depth (fumi-men 踏み面, ‘tread surface’), rise or riser (ke-age 蹴上げ, ‘kick up’), and ‘kick board’ (ke-komi-ita 蹴込み板).

A ‘box stair’ (hako-kaidan 箱階段) with parts labelled: upper floor (ni-kai yuka 2階床), stair beam (kaidan-uke bari 階段受けばり), tread board (dan-ita 段板 or fumi-ita 踏み板), stringer (gawa-ita 側板), and ‘back boards’ (ura-ita 裏板).

*Because the definition of the term ‘first floor’ differs between Anglophone countries, in this series of posts I will try to stick to the terms ‘ground floor’ and ‘upper floor’ to avoid confusion. The Japanese concords with the American naming convention: the ground floor is the ‘first floor (ikkai 一階, lit. ‘one level’); the floor above that is the ‘second floor’ (nikai 二階, lit. ‘two level’), and so on.