After looking at the features of the ‘living room’ (hiroma 広間) and the somewhat more formal ‘drawing room’ (dei 出居) of the minka, from this week we will consider the elements typically found in, and characteristic of, the formal room proper: the zashiki (座敷).

The regular or ‘classic’ zashiki draws its design elements from the stream of the shoin-zukuri (書院造り), the residential architectural style of the Muromachi era (Muromachi jidai 室町時代, 1336 -1573) samurai (bushi 武士) class, and was furnished with a decorative alcove (tokonoma 床の間, often abbreviated to toko 床), ornamental shelves (tana 棚), and shoin (書院, a decorative ‘study' or ‘desk' alcove adjacent to the toko) as a general rule. Then a picture rail (nageshi 長押) was run around the room above the ‘door’ heads (kamoi 鴨居), with ornamental hardware (kugi-kakushi 釘隠し, lit. ‘nail hider’) attached; and ornamental panels inserted into the transom (ranma 欄間) between rooms. These panels might be kumiko (組子, geometric patterns formed with tiny pieces of timber), fretwork, or ita-ranma (板欄間), thin boards of around 12 mm thick carved with images or patterns. The ceiling ( tenjо̄ 天井) is sao-buchi tenjо̄ (竿縁天井), a ceiling of thin timber boards on exposed battens (sao-buchi 竿縁).

A zashiki seen from the ‘second room’ (tsugi-no-ma 次の間), showing ornamental alcove (toko-no-ma 床の間), ‘study’ alcove (shoin 書院), squared-log post (men-kawa bashira 面皮柱), picture rail (nageshi 長押) with ornamental ‘nail hiders’ (kugi-kakushi 釘隠し), and fine carved transom panels (ranma 欄間) between the rooms and between the tsugi-no-ma and ‘verandah’ (engawa 縁側). Yoshimura house (Yoshimura-ke 吉村家), О̄saka Prefecture, designated an Important Cultural Property.

The ‘facade’ interior elevation of a large, high-ceilinged zashiki. A good archetypal example, with: decorative alcove (tokonoma 床の間), left, displaying hanging scroll; a ‘flanking alcove’ (toko-waki 床脇), centre right, with staggered shelves (chigai-dana 違い棚) and upper cabinets (tenbukuro 天袋); a ‘study’ or ‘desk’ (shoiin 書院), right; a fine lattice transom (ranma 欄間), top left, above the entry opening; a picture rail (nageshi 長押) running around the room at head datum (uchi-nori 内法) height; an ornamental metal ‘nail hider’ (kugi-kakushi 釘隠し) on the nageshi where it meets the tokonoma post (toko-bashira 床柱); and a board and batten (sao-buchi 竿縁) ceiling.

Another zashiki, with many of the same elements shown in the zashiki above. The half-glazed shо̄ji, left, indicate this to be a relatively modern example.

In the prototypical or archetypal minka layout, there is no true formal zashiki, but even in simply-partitioned minka without a formal room, the word zashiki was sometimes used as the name of the everyday living room, elsewhere called the hiroma or dei. In the most general sense, zashiki can refer to the raised floor (taka-yuka 高床) living part (kyojū bubun 居住部分) of the dwelling, as opposed to the earth-floored utility space (doma 土間).

With rising living standards and the emergence of an economic surplus, formal zashiki came to be constructed in the houses of commoners in imitation of the upper classes, but these ‘aspirational’ zashiki were unreflective of the lifestyles of the still-impoverished farmers who installed them; often the tatami mats, so characteristic of zashiki, were taken up and left unused, indicating that in everyday use the room was being employed for less-than-formal purposes, and the inhabitants wanted to protect the valuable tatami from damage. Even if the zashiki contained a tokonoma, it might not have been used to display any of the decorative art or craft works found in the tokonoma of wealthier homes. At best there might be a hanging scroll (jiku 軸) dedicated to the god Amaterasu О̄kami (天照皇太神); at worst the tokonoma might have even fallen to the status of a place to store the tatami mats.

There were many regions in which some or all of the above-described elements of the typical zashiki were prohibited by sumptuary law from being installed in the houses of peasants, farmers, or general commoners, effectively meaning that the zashiki itself was forbidden to these social classes. But the frequency with which these regulations were issued suggests that people were constantly building these features anyway, in defiance of the law. We can sympathise with these farmers, living under an enforced and artificial austerity, wanting to beautify their homes or ‘keep up with the Joneses’, even to the point of risking presumably harsh punishments.

In constrast, important figures such as village headmen and ‘chief executives’ (肝煎 kimo-iri) were obliged to receive or entertain officials (yakunin 役人) of the samurai class in the course of their duties, so zashiki were a necessity in their homes, and facilities such as toko and tana were permitted to them. It was not unusual for such zashiki to also contain a jо̄dan no ma (上段の間), a ‘room within a room’ whose floor level is a step above the floor level of the zashiki. In addition to the toko and tana, there would normally also be a shoin, picture rail (nageshi), ‘wraparound verandah’ (mawari-en 回り縁), and perhaps a separate ‘upper toilet (kami-benjo or uwa-benjo 上便所). The mawari-en served as the formal entrance and exit for officials, doctors and others.

The zashiki in the typical four-room layout farmhouse minka occupies the upper (kami-te 上手, i.e. furthest from the doma), facade-side (omote-gawa 表側) quadrant; in hiroma-gata layouts, both upper rooms may be zashiki, called kagi-zashiki (鍵座敷), perhaps with one built as an extension off the main structure, forming the rear leg of an L-planform. A toko built against the uppermost gable end (tsuma 妻) or short-side wall is called a tsuma-doko (妻床, ‘gable-end toko); if built at the rear of the zashiki, on the partition wall with the bedroom (nando 納戸), it is called a hira-doko (平床, lit. ‘flat toko’). In the case of kagi-zashiki, the upper and lower zashiki are open to one another and together take up the whole width of the building from facade to rear, so the toko is often a hira-doko, built on the rear wall of the rear zashiki. Shо̄ji (障子, translucent paper-covered timber lattice sliding panels) or fusuma (襖, light, opaque sliding panels) were used at the boundary between two zashiki, but between zashiki and everyday living spaces such as the oe (おえ) or hiroma (ひろま), obi-to (sliding partitions of solid timber panels with a mid rail) were used, indicating that women in labour and menses (akafujou 赤不浄, lit. ‘red unclean’), those in mourning (kurofujou 黒不浄 lit. ‘black unclean’), and people of low status were not enter the zashiki without good reason.

A regular four-room layout (seikei yon-madori 整形四間取り), showing the zashiki (ざしき) in the upper (furthest from the earth-floored utility area niwa にわ) front (facade-side) quadrant, with gable-end (tsuma 妻) decorative alcove (toko とこ), called a tsuma-doko (妻床), and adjacent Buddhist alcove (butsuma 仏間). Toko and butsuma are contained in a lean-to structure outside the perimeter of the main building.

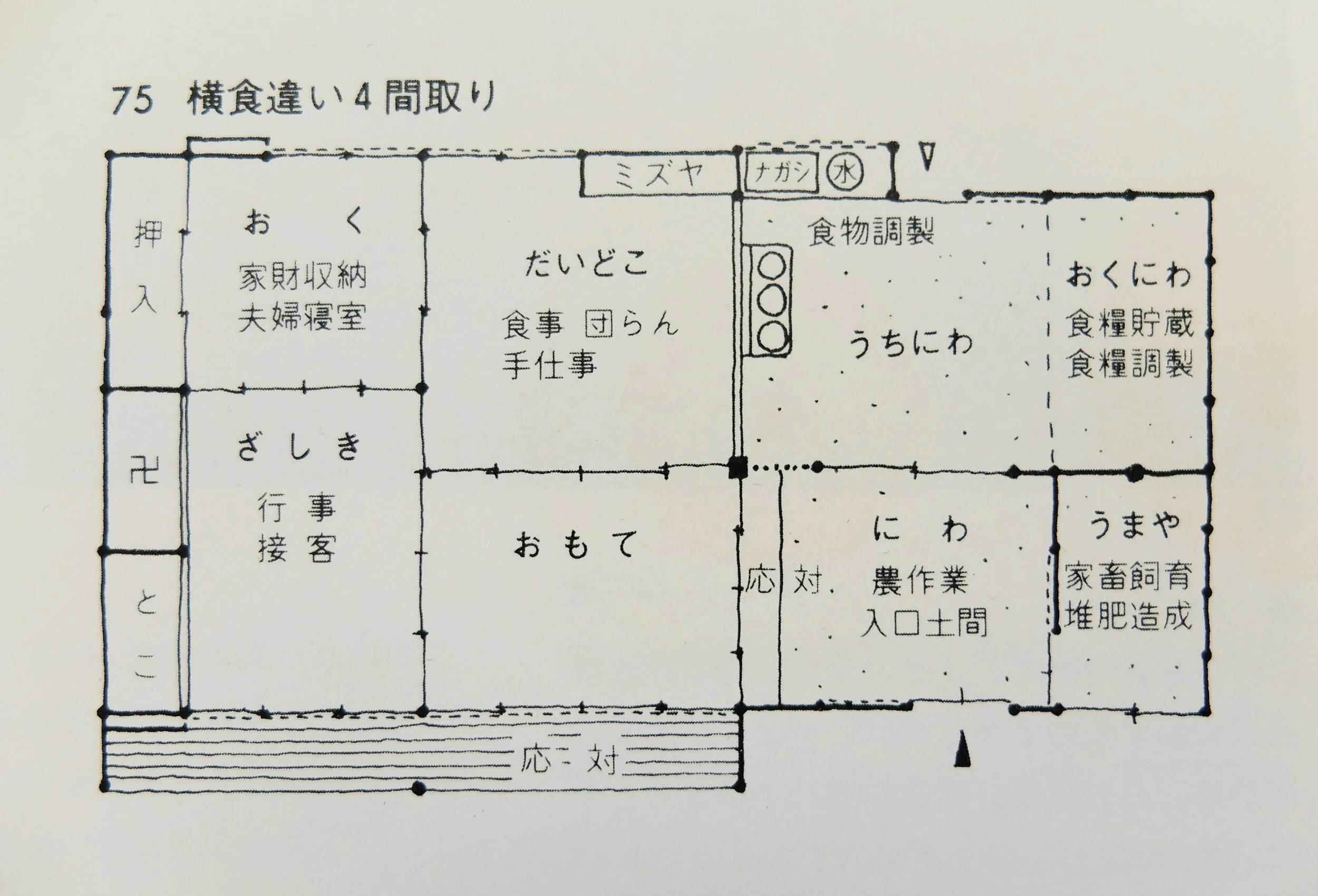

Another example of a gable-end toko (tsuma-dokoi 妻床), this time in a ‘perpendicular stagger’ (yoko-chigai-gata 横違い型) four-room layout (yon-madori 四間取り). The blind gable end (tsuma 妻) is entirely taken up with toko (とこ) and butsuma (卍) in the zashiki, and closet (oshi-ire 押入) in the rear bedroom (oku おく).

This regular four-room layout shows the minka in its original form, with a Buddhist alcove (butsuma, 卍) and cupboard (todana 戸棚) between the zashiki (ざしき) and bedroom/storage room (nando なんど); later a gable-end toko (tsuma-doko 妻床) was added as a lean-to structure, shown as a dashed line outside the exterior wall line of the main building.

This ‘wrapped hiroma’ (tori-maki hiroma-gata 取巻き広間型) layout, originally a front-zashiki three-room layout (mae-zashikisan-madori 前座敷三間取り) to which a rear kagi-zashiki (here ‘upper zashiki’ kami-zashiki かみざしき) has been added. This example solves the problem of where to place the tokonoma by omitting it.

A minka with two zashiki: the front zashiki, here called toba-no-ma (とばのま), and the rear kagi-zashiki, here called the oku (おく). The oku contains a long-side toko (hira-doko 平床), and next to it a storage closet (mono-ire ものいれ). The Buddhist alcove (butsuma, marked with swastika manji 卍), is in the room named zashiki (ざしき), which confusingly is not the formal room; at best it is semi-formal, used for courting/socialising (kousai 交際) but also for rearing silkworms (chisan shi-iku 稚蚕飼育).

Another example of a kagi-zashiki layout, this one regular (seikei 整形), with front zashiki (mae-no-zashiki まえのざしき) and rear zashiki (oku-zashiki 奥座敷). Here, the name mae-no-zashiki actually covers two rooms: the formal zashiki proper in the front upper quadrant, and a less formal ‘living room’ (ima 居間) in the front lower quadrant, adjacent to the earth-floored utility area (daidoko だいどこ). A wraparound verandah (mawari-en 回り縁) connects these three rooms; in the oku-zashiki there is a shoin, here called an akadoko (アカドコ), next to the toko, projecting out into the mawari-en.

In the postwar period, even in normal farmhouses, the tatami mats in the zashiki were left in place, but the zashiki came to function less as a formal room and more as a living room and bedroom for the elderly members of the household or for children. The tokonoma was even used as a television alcove — a utilitarian echo of the pre-modern practice of using the toko as a place to store tatami mats.

The zashiki of a rustic minka in the Tо̄hoku region. The tokonoma (床の間, left) is bare; the toko-waki (床脇) space next to the tokonoma is occupied by the Buddhist altar (butsudan 仏壇); there is no ceiling, picture rail (nageshi 長押), or separate ‘attached door heads’ (tsuke-kamoi 付鴨居); instead, grooves to take the sliding partitions are cut directly into the lintel beams. Former residence of the Fujiwara family (Fujiwara-ke 藤原家), Iwate Prefecture, now relocated to the Open Air Museum of Old Japanese Farmhouses (Minka Shuuraku Hakubutsukan 民家集落博物館), О̄saka Prefecture.