The ovolo is the simplest of the convex mouldings: its profile is a simple arc, usually of 90 degrees. The uniform change in angle produces a correspondingly smooth shadow gradient: whether the ovolo faces up or down, the shadow transitions from light at the top to dark at the bottom.

The convex ‘bulge' of the ovolo gives it a robust, dependable character; whether supporting a cornice or sitting at the base of a column or wall, it expresses a sense of resistance to gravity and muscular deformation under load.

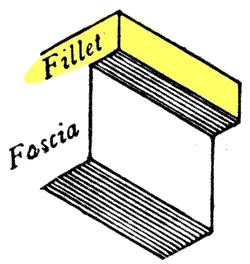

Like the fillet and the fascia, the ovolo is still in common use, chiefly as the small timber moulding known as a quad, which is used to cover joints at 90 degree changes of angle such as that between a external brickwork and the eaves soffit, between a wall and kitchen cabinets, or as cheap skirtings or cornices in utilitarian rooms like toilets or laundries.